Chapter 13: Self-Talk

“People are disturbed not by things, but by the views which they take of them.”

Epictetus, first century A.D.

“If people stopped looking on their emotions as ethereal, almost inhuman processes, and realistically viewed them as being largely composed of perceptions, thoughts, evaluations, and internalized sentences, they would find it quite possible to work calmly and concertedly at changing them.”

Albert Ellis

“Crises marked by anxiety, doubt, and despair have always been those periods of personal unrest that occur at the times when a man is sufficiently unsettled to have an opportunity for personal growth. We must always see our feelings of uneasiness as being our chance for making the growth choice rather than the fear choice.”

Sheldon B, Kopp paraphrasing Abraham Maslow

This is a lengthy chapter as it is transformational. Becoming mindful of your self-talk to the point that you are no longer controlled by your thoughts and beliefs, is central to becoming a masterful relationship partner.

Consider the Epictetus quote above. It may be that what's upsetting you is not really what your partner is doing, has done, is saying or has said. It may be that what you are telling yourself is what's driving your reaction.

We all do it. We all deny, distort, and falsify reality, particularly when strong emotions have been activated. When your attachment needs are not being met, when your partner has turned away from you, or seems to be in attack mode, you may find your amygdala hijacked and your fight or flight mode activated.

Please be aware that you have three choices when you interact with your partner. You can turn toward your partner with interest, empathy and understanding. You can turn away from your partner with indifference, or you can turn against your partner with anger. When you're in the middle of an "amygdala hijack" you are more likely to turn away from your partner or against your partner and you have greatly diminished capacity to see the situation clearly and objectively.

It starts with your perception of what's going on and what you are telling yourself about what you are experiencing. Your reaction begins with your self-talk.

We often disturb ourselves, deepening and prolonging our relationship distress with learned negative self-talk and maladaptive core beliefs. Engaging in self-reflection and dealing with negative self-talk and distorted thinking with awareness, acceptance, defusion, and more realistic self-talk, is a key to transforming a relationship characterized by stress, anxiety, depression, anger or resentment to a relationship that is dramatically more satisfying.

Strategies and skills for not letting negative self-talk and maladaptive core beliefs dominate your life are discussed in this chapter. Let’s again check in with Matt.

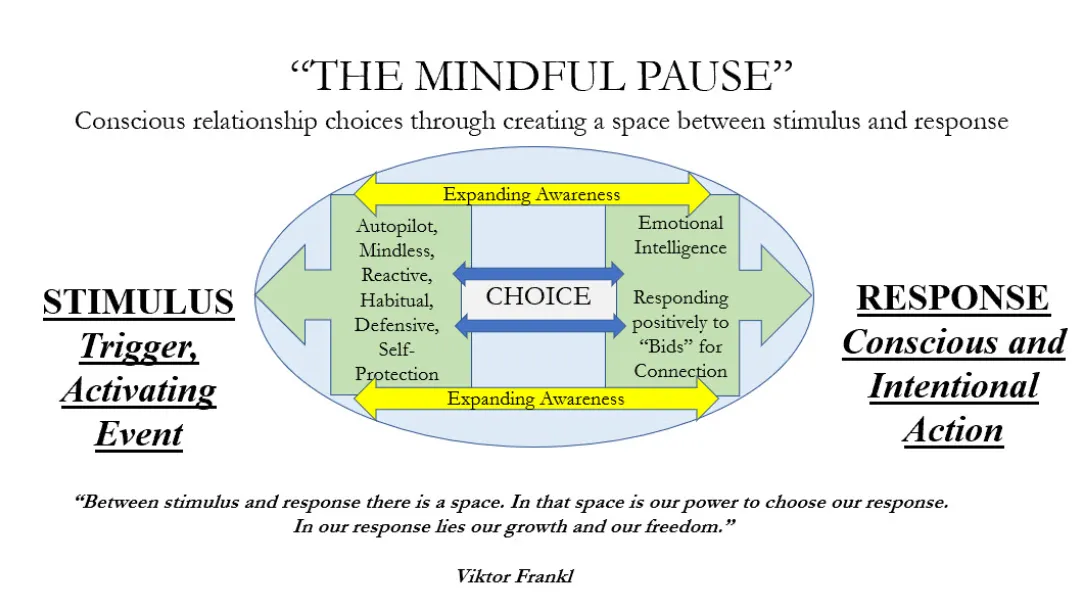

Matt was deep in thought as he entered the final leg of his ride home. The traffic was heavy – typical for a Monday but he was running an hour later than usual. However, the sun was shining, the temperature was great, sales were up, all the stats were positive, things were good with the kids , and for the moment things were peaceful with Beverly. – so, what was it then? He had learned deep breathing in his therapy sessions and was faithfully following suggestions. It was helping. Reminding himself to take three deep diaphragmatic breaths when feeling stressed kept him from feeling perpetually "frazzled" – his term for the state of near panic that until recently was becoming an ongoing condition. Moreover, he was now able to be aware of his level of stress and anxiety on a 1 to 10 scale, and to use awareness of rising anxiety as a reminder to breathe and "take it down a notch or two." It worked! But still... His therapist had talked about self-calming skill being in two parts, deep, slow, regular abdominal breathing, or "belly breathing," along with defusing and redirecting self-talk — diaphragmatic breathing coupled with self-soothing inner dialogue. She said that doing one without the other was like driving your car with one foot on the accelerator and the other foot on the brake – not an effective way to drive, and probably not good for the equipment either. It was that second part, the self-talk. I've always been hard on myself, Matt thought, but that's just the way I am. If I don't push myself, I'll fall short of my goals. I might even lose my job. Where would that leave Bev and the kids? Of course! I've got to beat up on myself from time to time. It's all that keeps me from being mediocre. How else can I see it? I'm not sure I understand this self-talk thing. Lately there had been tension with Beverly. She complained that he often seemed distracted, overly focused on work. She wanted more of his time and wanted him to spend more time with the kids. Couldn't she see how hard he was working? Matt was hoping it wouldn't be another one of "those discussions.” He just wanted a peaceful evening. Pulling into his driveway Matt reminded himself to take three more deep breaths, immediately feeling his body respond with a wave of relaxation. Yes, it was working. Feeling un-characteristically calm, Matt put on his happy face and headed through the front door. "I’m home Bev," he said, walking briskly into the kitchen. Beverly glanced up from bags of groceries she had just brought in from the car. "I wish you would have been here earlier. I have a lot to do getting dinner going for you and the kids. I could use a little more help around here. Where are you when I need you?" “Traffic!” Matt managed to get that one word out before Beverly added angrily: "I feel like I'm all alone here. You're always late. I don't know why you can't leave earlier and beat the traffic." The “wave of relaxation” quickly crashed on a rocky shore. Instantaneously heart rate and respiration accelerated as angry thoughts poked their way into Matt’s consciousness. He wondered if it was going to be another difficult evening. What if we're going to get into another argument? What if she’s unhappy with me for the rest of the evening? What if...? Taking three deep breaths Matt headed to their bedroom to change clothes, his mind racing with "What if?" thoughts, and smoldering with anger and resentment — and the anxiety was back full force. Unconsciously his breathing was becoming more rapid and shallow. He caught himself once again and reminded himself – breathe! The breathing was helping, but it was a struggle to keep the anxiety at bay. Struggling for calm and clear thinking, Matt tried to remember – what was that about brake and accelerator? Matt needs practice. He's learned that he can calm himself by moving his center from his upper chest to his belly and breathing diaphragmatically. He also knows that his self-talk is part of the problem. However, the practice component is necessary to form a new habit, automatically pairing diaphragmatic breathing with self-soothing self-talk. Otherwise, it may very well be "one foot on the brake and one foot on the accelerator." With practice Matt will become really good at using his emotional arousal as a cue to plug-in a learned relaxation response and switch to more realistic self-talk. With practice Matt will learn to take a "mindful pause" and respond with emotional intelligence and self-talk that will help him with any relationship issue. Figure 18-4: The Mindful Pause Let's revisit the MCC self-assessment with Choice 4, Self-Talk. This time, as you rate yourself, you'll also see our thoughts behind the statement. Your ratings may have changed since the last time. That's okay. In fact, that's what we expect. This is a program of assessment-based continuous improvement toward being truly masterful in how you show up in your relationship. Self-assessment is vital. Score yourself before you look at the thoughts behind the statement. Self-Talk Self-Assessment DIRECTIONS: Under each description, choose the number that best represents agreement with your behavior for the past week. Record the number that best applies on your Mindful Choices for Couples Self-Assessment Scoring Sheet. 0 = not true at all, or 0 percent; 1 = mostly not true, or 25 percent; 2 = partially true, or 50 percent; 3 = largely true, or 75 percent; 4 = totally true, or 95–100 percent 6. SELF-TALK |

a. I Am Aware of the Thoughts and Feelings Connection. I am aware the unpleasant emotions I experience often stem from views I have of the situation and beliefs learned in my childhood and from earlier life experiences. I am becoming more aware of my emotional reaction to my partner and I'm linking that reaction to my self-talk.

Select 0, 1, 2, 3, or 4 and record on your Mindful Choices for Couples Self-Assessment Scoring Sheet.

The thoughts behind the statement.

The actual situation is often less important than what we are telling ourselves about the situation. Beliefs we have carried with us for years, perhaps from before your present relationship, perhaps even from early childhood, have a profound effect upon how we view the present situation. Stress and anxiety, along with feelings such as fear, sadness, anger, dread and despair often result from learned beliefs and expectations.

Janice was in near constant turmoil. Her relationship with Patrick was only three months old yet the source of much anxiety and insecurity. She had strong feelings for Patrick and believed he felt similarly, although they hadn't yet used the "L" word. When Patrick was away from her for an extended period of time, or was slow to return her calls, she told herself that he didn't care and was probably seeing someone else. Her previous boyfriend had cheated on her and she was deeply wounded. She found it very difficultto relax and enjoy a developing relationship.

b. I Am Mindfully Aware of My “Stories.” During my day, there are instances where I am able to slow down my thinking and become more aware, or more "mindful," of my thoughts, accepting those thoughts as only "stories" my mind is telling me, and not necessarily useful, valid, or the stuff of objective reality. I am aware of “hidden agendas“ and able to instead act on deeper needs and values such as my need for connection and my valuing of our relationship .

Select 0, 1, 2, 3, or 4 and record on your Mindful Choices for Couples Self-Assessment Scoring Sheet.

The thoughts behind the statement.

“Mindful awareness,” is readily accessible by doing a mini relaxation, or engaging in the “Three Deep Breaths” Thomas Crum writes about in his excellent book by the same name. Breathing diaphragmatically with slow, deep, regular, quiet, and gentle breaths allows you to get out of “fight or flight” mode and into a state of heightened awareness of your own thoughts. While relaxed, focused, and centered, you can remind yourself that your thoughts are only thoughts, or stories that your mind is telling you. These stories are just that – stories – and need not be accepted as objective reality.

You may be only dimly aware of hidden agendas that are based on your need to protect your ego or avoid emotional pain. Stories are habitual knee-jerk autopilot reactions on the path of self-protection. While on that path your stories are characterized by hidden agendas.

Figure 18-1: Hidden Agendas

“The highest possible stage in moral culture is when we recognize that we ought to control our thoughts.”

― Charles Darwin

c. I Am Combining Self-Calming Skills with Mindfulness. During my day I regularly pay attention to everything going on inside myself (thoughts, feelings, breathing patterns, and bodily sensations), as well as outside. This is done in conjunction with self-calming through diaphragmatic breathing and purposefully relaxing tensed muscles. Self-calming skills give me the opportunity for a "mindful pause "between stimulus and response within which to observe my self-talk and make a course correction.

Select 0, 1, 2, 3, or 4 and record on your Mindful Choices for Couples Self-Assessment Scoring Sheet.

The thoughts behind the statement.

Regularly do a mind-body scan. As often as necessary, you can choose to calm down, slow down, relax, and give up having to do anything, choosing instead to engage your well-practiced self-calming skills, turning inward and observing your own thoughts, feelings and bodily sensations. You might consider doing this once an hour, or perhaps every time you perform some routine act like having a drink of water, coffee, or tea. Certainly, you can check in with yourself every time you become aware of distressing thoughts or unsettling emotions. We suggest putting a number from 1 to 10 on your feeling of stress or anxiety, and plugging in your learned relaxation response each time you become aware of rising levels of distress.

“This "mind-body scan" also includes checking in with your self-talk. Your mind is not always your friend and it's important to learn how to observe your self-talk and decide if it's useful or helpful. This kind of introspection is only possible when you have first taken the time to calm down, slow down, give up judgment, and consciously choose self-talk better suited to your relationship needs.

Observing your self-talk calmly and mindfully gives you the opportunity to create a "mindful pause," a space between stimulus and response in which to choose an emotionally intelligent response.

d. Distressing Situations Provide Me with Constructive Learning Experiences. I am able to revisit distressing situations, understanding those situations and my reactions to them through an understanding of the role of my self-talk and beliefs. (Note: circle 4 if there are no "distressing situations."

Select 0, 1, 2, 3, or 4 and record on your Mindful Choices for Couples Self-Assessment Scoring Sheet.

The thoughts behind the statement.

We all have stress, anxiety and sometimes distressing relationship situations. Such situations, although difficult and alarming, can be valuable “learning opportunities,” giving you an opportunity to mindfully reflect on the situation and gain important insights that will be helpful in the future. Most of the distressing situations in your life will get repeated, and your reactions may be habitual and stereotyped, a quality we refer to as “mindless.” Sometimes your usual pre-programmed reactions are helpful, but often they create more difficulties. When you can take the time to reflect and learn, you gain the ability to be conscious and intentional rather than mindless and on autopilot. You can move from mindlessness and reactivity to mindful awareness and positive new behaviors.

Mistakes are valuable. That's how you learn. When things don't go well, you have an opportunity to look back on a constructive learning opportunity. You will never be perfect at being in relationship. You will simply be much better and much more satisfied.

With repetition of this kind of self-reflection and conscious processing of experience, positive relationship habits are created and strengthened. The good news about bad habits is that they were learned, and anything that you've learned can be relearned. As new learning is repeated, it becomes habitual.

e. Constructive Inner Dialogue. When feeling stressed or anxious, I check in with myself by taking several diaphragmatic breaths and engaging in an internal dialogue. The following are examples of some possible questions I might ask myself.

Select 0, 1, 2, 3, or 4 and record on your Mindful Choices for Couples Self-Assessment Scoring Sheet.

The thoughts behind the statement.

- What am I telling myself about my coping ability? What do I perceive to be a threat?

- What am I feeling? What are my emotions?

- What's going on in my body? What is my physical experience?

- What am I telling myself that is not accepting or compassionate?

- Are there things I can't control? Are there things I can control?

- Can I be more accepting and compassionate toward myself? What would I be telling myself if I were more compassionate?

- Can I be more compassionate toward my partner? Can I see beyond anger to underlying feelings and unmet needs?

- Am I aware of my partners "bids for connection," and am I able to respond positively.

- Am I aware of opportunities for connection?

- Do I have needs that are not being met? Do I have boundaries that are not being observed, or asserted?

- Am I being realistic? Am I engaging in "what if thinking," or "awfulizing" or “catastrophizing?"

- What are my choices? What options am I aware of when I view my situation from a position of calmness and self -acceptance?

(Note: circle 4 if there were no instances of feeling "stressed or anxious.")

Diaphragmatic breathing practiced to the point of being routine is almost always helpful in calming yourself and moving beyond emotional reactivity. High levels of stress and being in “fight or flight” mode often result in impaired judgment and poor decisions. For one thing, when you are in fight or flight mode you only have two options, fight or flight, neither of which is likely to result in helpful choices. Moving to a more relaxed and aware state gives you the ability to engage in a constructive inner dialogue. The sample questions above represent things you can ask yourself to bring about greater clarity, less reactivity, and more positive and realistic outcomes. Be mindful of when you are in fight or flight mode, and never proceed until you have moved from your sympathetic system to your parasympathetic system.

Emotional intelligence has been a popular concept in recent years. It’s about being intelligent in managing your emotions, rather than being managed by your emotions. Mindful awareness is how you do emotional intelligence and diaphragmatic breathing and checking in with yourself is the easiest and most direct way to activate mindful awareness. Emotional intelligence involves engaging in inner dialogue, asking yourself questions such as the sample questions above, and finding objective answers rather than emotion driven reactivity.

Select 0, 1, 2, 3, or 4 and record on your Mindful Choices for Couples Self-Assessment Scoring Sheet.

The thoughts behind the statement.

f. I Actively Demonstrate My Belief in My Self-Worth and My Belief in My Partner’s Self-Worth. In thought and behavior, I demonstrate my belief that we are both worthy of love and respect.

Select 0, 1, 2, 3, or 4 and record on your Mindful Choices for Couples Self-Assessment Scoring Sheet.

The thoughts behind the statement.

Low self-acceptance, a lack of self-compassion, and a lack of assertiveness often originate in long-held beliefs about not being good enough, worthy enough, competent or lovable. Such beliefs inevitably result in greater distress. Anxious attachment styles that further reinforce the negative beliefs

It’s a vicious cycle. Often these beliefs are unconscious, or such a solid part of one’s worldview that change is stubbornly resisted. Relationship difficulties arising from negative self-talk about yourself and your partner intensify insecurity’ and emotional reactivity. In terms of adult attachment styles, negative self-talk reinforces being anxiously insecure, avoidantly insecure, or having a chaotic attachment style with a mixture of fearfulness and avoidance.

However, with mindful awareness such beliefs and self-talk become fully conscious. It then ebcomes possible to simply acknowledge the existence of faulty beliefs, calmly and without exaggerated reactivity, choosing instead to move in an entirely new direction, a direction that is freeing, self-accepting, self-compassionate, and self-affirming.

g. I Am Eliminating Negative Self-Judgment and self-blame. I don’t tell myself that I am flawed, defective, unlovable, or basically incompetent. I don’t dwell on what I perceive to be failures or mistakes, believing instead that mistakes help me learn and I am able to forgive myself for mistakes or failures.

Select 0, 1, 2, 3, or 4 and record on your Mindful Choices for Couples Self-Assessment Scoring Sheet.

The thoughts behind the statement.

We ask almost every new client the same question: “Inside your head, when you are thinking about yourself, is your self-talk harsh, nagging, and critical, or is it warm, encouraging, and accepting?” What we have noticed with the great majority of our highly stressed and anxious clients, and those suffering from depression as well, is a high level of negative self-talk about self, coupled with highly critical self-judgment. In short, the people we see with “dis-ease” are rarely nice to themselves.

Learning to be self-accepting and self-compassionate are key ingredients in good mental health and a sense of well-being. These qualities are not obtainable until you can become mindful of your negative self-talk and make a conscious choice, moment by moment, to simply be kind to yourself in the way you think about yourself and talk to yourself. And yes, we all talk to ourselves.

Mistakes are valuable. They inform us. They educate us. They are indispensable in our learning and our growth. Stressed, anxious, and depressed people are often beating themselves up over what they perceive to be irreversible and unpardonable failures. They often feel ashamed and guilty, hiding their mistakes, denying they are mistakes at all, or shifting the blame onto others. More secure people on the other hand simply accept their mistakes as inevitable and even see them as opportunities for new learning and growth. They might choose to tell themselves: “It is what it is,” accepting the reality that mistakes happen, choosing to learn, let go, and move on. It helps to remind yourself that mistakes are human, that you’re human, and one with all humanity – all of us are imperfect and mistake prone.

Practicing self-compassion is magical. You will transform your life greatly reducing depression and anxiety. Just as important, with self-compassion you will find it much easier to be compassionate toward your partner. When being a flawed human being, like all other human beings, is okay, you will find it easier to accept your partner as another flawed human being whom you can love and respect anyway. Try it! It's quite liberating.

h. I have core beliefs and helpful assumptions that guide me in my dealings with my partner. I believe that conflict is inevitable, that both of us have valid goals, that we need to understand each other rather than have agreement at all costs, that we can both win, and that conflict is an opportunity to grow our relationship.

Select 0, 1, 2, 3, or 4 and record on your Mindful Choices for Couples Self-Assessment Scoring Sheet.

The thoughts behind the statement.

When taking a "mindful pause" I remind myself of things I know to be true about my relationship. My self-talk shifts to relationship enhancing thoughts as I remind myself of my basic intentions for the relationship. I remind myself that conflict is inevitable because we are to different people even though we have much in common. I remind myself that you are not wrong simply because you see your world differently. I accept the responsibility to understand your unique awareness of your world, putting my own beliefs on the back burner. I remind myself to practice one of Stephen Covey's "Seven Habits of Highly Effective People," seek first to understand and then to be understood. I remind myself that we may not agree but we do have to understand one another, and deal with one another respectfully.

Adopting a belief that conflicts represent opportunities for growth is a hard sell for many people. However, if you're open to it, approaching conflicts in an open, willing to learn, nonjudgmental manner as described in this book can put you on a path toward being highly skilled as a relationship partner.

Conflicts are valuable. They inform us. They educate us. They are indispensable in our relational learning and growth. People who don’t deal well with conflict are often blaming their partners or beating themselves up over what they perceive to be irreversible and unpardonable failures. They often feel ashamed and guilty, hiding their mistakes, denying they are mistakes at all, or shifting the blame onto others. More secure people on the other hand simply accept conflict as inevitable and even see conflicts as opportunities for new learning and growth. They might choose to tell themselves: “It is what it is,” accepting the reality that conflict happens, choosing to learn, let go, and move on.

Figure 18-2: Helpful Assumptions

i. I am willing to take risks. I will not avoid opportunities to make a bid for connection out of fear of being rejected or criticized. I will let you know what I think, what I feel, what I want, and what I need. I recognize self-talk that leads me to be either unassertive or aggressive with you. I engage in corrective self-talk and let you know where I'm coming from, respectfully, calmly, and assertively.

Select 0, 1, 2, 3, or 4 and record on your Mindful Choices for Couples Self-Assessment Scoring Sheet.

The thoughts behind the statement.

The most successful relationship partners aren’t afraid to take calculated risks, and they are not afraid to be vulnerable.. They don’t hold back because of fear of failure or concerns about what their partner might think. They let go of having to be perfect or needing to be above making mistakes. They see themselves as a work in progress and maintain a curious and optimistic view of the possibilities unfolding before them, rather than fearing dire consequences and harsh judgments. They don’t waste time in comparing themselves to others, instead choosing to focus on their own lives as interesting journeys of self-discovery and growing self-mastery.

j. I Engage in Realistic Threat Appraisal. I am able to ask myself what the worst thing is that could realistically happen in my relationship, and quickly determine that if and when that circumstance took place, I will be able to handle it. I do not hold back because of fear, self-doubt, or expectations of failure or defeat, and I do not over-react with defensiveness, avoidance, anger, resentment, or other exaggerated protective responses.

Select 0, 1, 2, 3, or 4 and record on your Mindful Choices for Couples Self-Assessment Scoring Sheet.

The thoughts behind the statement.

Most people don't like conflict, and they especially don't like all out fighting. We're guessing you don’t like it either.

In fact, this book isn't meant for people who enjoy venting their anger or fighting to win at all costs. This book is for you if you want to build a relationship and be masterful at contributing to a relationship that works for both of you.

Sometimes fear gets in the way, fear of rejection, fear of abandonment, fear of being imperfect, or fear of failure. You will remember from our discussion of adult attachment styles that many people are either anxiously insecure or avoidantly insecure, either pursuers or withdrawers. In either case relationship damaging self-talk exacerbates basic fears and shines a spotlight on unmet attachment needs.

A very useful strategy for dealing with feared situations is asking yourself: “What’s the worst thing that could realistically happen?” The emphasis is on the word “realistic.” For many people the focus is on the worst thing that could “possibly” happen, believing that if it could happen it surely will happen and must be defended against at all costs. The more extreme your reaction to perceived threat, the more your partner is likely to withdraw or attack. Another vicious cycle!

Telling yourself something is really scary, or even terrifying, propels you into high anxiety and limits your ability to think rationally and objectively. That’s when you start telling yourself even more disturbing things in an inner dialogue we refer to as “awfulizing,” or “catastrophizing.”

It’s hard to sort this out and regain your equilibrium when you are uptight and in fight-or-flight mode. This is where learning mindfulness skills and self-calming skills such as diaphragmatic breathing comes to the rescue. With self-calming skill and mindful awareness, it becomes easier to base your actions on evidence-based probabilities rather than baseless scare-talk within your own head.

Respond to threats realistically. Determine if they are real or imagined. Corrective self-talk is vital — self-talk that is realistic, self-soothing, and supportive of a healthy relationship.

Extended Discussion of “Self-Talk”

"The most fundamental aggression to ourselves, the most fundamental harm we can do to ourselves, is to remain ignorant by not having the courage and the respect to look at ourselves honestly and gently."

Pema Chodron

Your relationship is about choices, or to be more precise,choices that lead to a satisfying relationship, relatively free of "disfunction," and one that results from conscious choices based on mindful awareness. Such awareness incudes awareness of learned self-talk.

Corrective self-talk is vital. Relationship recovery and growth, and transformation to wholeness and vitality, regardless of the problem being addressed, cannot take place without developing mindful awareness of your own distortions.

We use a variety of tools in developing these qualities, always with the goal of empowering our clients to confidently and enthusiastically make healthy choices. These tools include methods of changing your self-talk and embracing beliefs that work for you rather than against you.

Did you know you can change your self-talk? Did you know you can change your beliefs? You absolutely can and it might be easier than you think.

A principal self-talk change tool that we have used over the years, and a tool that has been quick and easy to teach, yet highly effective, is a type of cognitive behavioral therapy that has been around for more than 60 years – RET or Rational Emotive Therapy. Rational Emotive Therapy (RET, an older version of what is now known as Rational Emotive Behavioral Therapy (REBT), provides a powerful and easily teachable method for healing and growth.

Mindfulness and conscious choice are the transformative qualities that underlie effectiveness in career, relationships, and overall well-being. Rational Emotive Therapy and other approaches such as ACT (Acceptance and Commitment Therapy), constitute powerful skills and processes for being mindful and consequently more self-aware and effective in self-management.

All of the problems we deal with are perpetuated and made worse by "mindlessness," a lack of conscious awareness, conscious intention, and conscious choice. Moreover, negative self-talk and "scare-talk" thrive in the absence of mindful self-awareness. The cultivation of mindfulness skill is a major part of the solution, and we use Rational Emotive Therapy as a major tool in bringing about a high level of self-awareness and effective self-management of distorted thinking.

However, in the interest of consistency in our practice, we have made some changes in the original RET structure to make the process compatible with the concepts of fusion and defusion from ACT (Acceptance and Commitment Therapy). We use RET as a way of training our clients to be fully aware of their irrational thoughts (don't be offended, we all have them), quickly getting to the point where they instantly recognize those thoughts before they lead to destructive behaviors. We use ACT, once clients become fully mindful of their self-talk, as a simpler version of quickly managing unhelpful thinking and beliefs

Before getting into the mechanics of how RET works, let's first take a closer look at what we mean by "distorted thinking."

What is Distorted Thinking? Chronic stress, compulsive behaviors, eating disorders, anxiety disorders, and most relationship problems require mindlessness and distorted thinking. This is not unique to those with these kinds of issues. All of us deny, falsify, and distort reality, and all of us are mindless at least some of the time. In fact, none of us are mindful all the time.

These are stressful times. Do you know anyone who isn't experiencing high stress, at least occasionally? How is your stress? How much do you worry? How much of your stress and worry has to do with your thoughts and beliefs?

We all have a lot going on in our heads. In fact, our minds cannot be still. Usually there are many things simultaneously competing for our attention in any given moment. Buddhists refer to a busy, directionless, untamed mind as a "monkey mind," and an untamed monkey mind will sooner or later get you in trouble. An untamed mind is a mind that distorts, obsesses, ruminates, and finds things to worry about.

Often, we put our own spin on things and see them in ways that may be highly inaccurate, yet these thoughts are embraced as absolute truth. This is normal. There is a natural tendency for us to accept our own thoughts as reality and to not recognize those thoughts as simply things we have learned to tell ourselves, stories our minds are telling us, stories that may not be true at all.

Be aware, if you are like virtually everyone else, you have a natural tendency to see your thoughts and beliefs as true reality. If your partner sees his or her world differently, they are clearly misinformed or irrational.

Again, we all have distortions, and we all have irrationalities. No matter how well put together you are, like everyone else, you deny, falsify, and distort reality on a fairly regular basis. We all do it. That’s because we are all human. None of us is a purely rational Mr. Spock (the pointy eared Vulcan from Star Trek not the pediatrician Dr. Spock).

Because you are human, you process information in accordance with your own set of beliefs. Many of these beliefs are “taught” beliefs, learned in your childhood from those who were closest to you and most significant in helping you meet your needs. Some of these beliefs are rather harmless, such as a belief staunchly held throughout life that you MUST always brush your teeth exactly as prescribed by mother, with absolutely no deviation allowed!

Sometimes however, these beliefs are destructive to your self-esteem and your relationships. You are often unaware of these beliefs at all, yet all too frequently you may feel overwhelmed by the unpleasant emotions that stem from them. You choose to think that it’s the event that you are reacting to without realizing that our feelings stem more from what we tell ourselves about the event than from what is actually happening.

In the words of the first century philosopher Epictitus: “People are disturbed not be things, but by the views which they take of them.” All of us have things happen to us. It's what we tell ourselves about what's happening that makes all the difference.

In fact, what we tell ourselves can make the difference between life and death. Sound dramatic? Consider the following examples of two women who have had similar experiences. Each has had her fiance suddenly break off the engagement and run off with her best friend. Each is emotionally devastated.

Susan had never before experienced such deep emotional pain. George was the love of her life and now he had broken off their engagement announcing that he had fallen for Susan's best friend. She was devastated. She knew it would be perhaps the most difficult undertaking of her life, but she knew she would ultimately recover. She knew that other people have been through similar difficulties, sooner or later getting their lives back on track and moving on to happier relationships. She knew that if she made full use of her support system, stayed busy, and took care of herself, she would in time move beyond this experience, and perhaps even grow in her coping abilities.

Susan's pain was real and extreme, yet she was realistic in her belief that people recover and ultimately get on with their lives. Susan will not only survive, she will grow with the experience and find a happier life.

Let's look at the example of Jane and how she dealt with similar loss and emotional pain.

Like Susan, Jane was devastated. She had never imagined that anything could hurt so much. She told herself that the pain was too much, too overwhelming, so much so that she would never get over it. There must be something really wrong with her for him to leave her. She could never love anyone that much again. No one would ever love her that way again. This was the only man she could ever be happy with, and now he was gone. She simply couldn't survive. There was nothing left to live for. It would never get any better. It was hopeless. She was hopeless. Jane chose suicide.

For both Jane and Susan, it was virtually the same situation and for both extremely painful. In Susan's case, her self-talk was quite rational. She knew her pain would take a long time to go away, but ultimately it would leave her and she knew she had to take care of herself in the meantime. Susan was in for a rough time but ultimately she would recover.

Jane's self-talk was predominantly irrational. She told herself she would never get over it and that she could never love anyone that way again, both irrational thoughts. Despite her certainty about the future, Jane didn't have a crystal ball and there was no way for her to know what was ahead. She might have talked to others about their experiences or consulted a therapist to gain a better perspective. Unfortunately, this didn't happen. Instead, she listened only to her own inner voice and didn't realize that her highly subjective inner dialogue only represented things her mind was telling her, things that were dangerously distorted and erroneous. Her other thoughts were similarly irrational and she unquestioningly believed all of it, and tragically with such conviction and finality that she perceived there was only one choice left to her, taking her own life.

As mentioned above, we all distort reality. We all have erroneous beliefs. We all disturb ourselves with negative self-talk learned early in life, and we each have a number of nutty thoughts that we cling to.

By way of an example, consider that only one of these irrational beliefs might be necessary to generate extreme disturbance.

Suppose you were one of those people who told yourself, and absolutely believed it to be true, “I must please everyone in everything I do, all of the time.” For one thing, it’s an impossible belief; no one can please everyone. There is bound to be someone that you disappoint in some way. In fact, there are many situations where a healthy person is bound to disappoint those around them if only to assert their boundaries and rights in a healthy way. You simply cannot be a person of good self-esteem, with a clear sense of your own identity and boundaries, and be a people pleaser who feels he or she “must” please those around them.

If you have such a belief and you are having a week in which everyone seems to be pleased, you are not off the hook. You are going to be preoccupied with the concern that someone might be displeased, that you might have failed to meet the needs of a family member, friend, or co-worker.

If however, you do find yourself displeasing someone, it will be grounds for depression and a sense of failure. Either way, you cannot win. By virtue of this one belief, you are destined to be either anxious or depressed all the time.

It gets worse. Others are quick to pick up on the fact that you are prone to guilt and anxiety if you fail to please them, and you are therefore, quite vulnerable to their manipulations. Because a corollary of this belief is that you cannot express anger (that would displease others for sure), you are going to be someone who stuffs anger and wears a smile on the outside. You will find yourself saying “yes” when you mean “no,” and others will often be quick to take advantage. Repeatedly taken advantage of, you may find yourself resenting other people and seeing others as problematic and a source of major anxiety. In the extreme, others will be perceived as so threatening that the only solution is to avoid them, leaving you with a sense of loneliness and isolation.

So, holding this one nutty belief leads not only to, anxiety or depression, but alsoleaves you feeling powerless, resentful, and with lowered self-esteem.

That was an example of having only one irrational belief. We all have many, and they occur in teams. People with chronic stress and anxiety usually have beliefs that keep them stuck in their disorder. Such thoughts are usually automatic and enter our consciousness with lightning speed. We are scarcely aware of the existence of these beliefs, if we have any awareness at all.

Much of therapy is aimed at helping our clients slow down their thinking and become more aware, in other words more mindful of their own distortions. Once this is done, they can begin to challenge those beliefs, plugging in more realistic and effective ways of viewing themselves and the world around them. They can begin to make different choices. This is vital to managing chronic stress, debilitating anxiety, and painful relationships that may be spiraling downward because of one's own negative self-talk.

In fact, it would be almost impossible to have chronic stress and anxiety without negative and irrational self-talk. Chronic stress requires stress generating self-talk, much of it learned in childhood, and intensified in adult life.

People remain stuck in anxiety by feeding into that anxiety with awfulizing and catastrophizing thoughts, ruminating on dreaded consequences in what we call "what if?" thinking that leads to "anticipatory anxiety." The quality anxious people most need is a well-practiced, calm and realistic approach to life. Again, Rational Emotive Therapy, along with Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, are major tools in bringing about this ability to mindfully pay attention to self-talk and make purposeful and effective choices. You can learn to recognize your self-talk as being only things your mind is telling you, and not necessarily true. Real progress in overcoming anxiety and stress results from learning to defuse the negative thoughts rather than embracing them as absolute reality.

With growing awareness, all that is necessary when your brain generates a disturbing thought, is to remind yourself that the thought is not useful and doesn’t have to be obeyed. This is the transition from RET to ACT. First however, let’s take a closer look at RET.

Rational Emotive Therapy (RET)

So what is Rational Emotive Therapy, or RET for short? It's a type of cognitive behavioral therapy that has been around for over six decades. It was developed by Albert Ellis, Ph.D., and Bill has fond memories of intensive training with Dr. Ellis at his Institute in New York City in the early 1970s. What at that time was RET, Rational Emotive Therapy, has since evolved into REBT for Rational Emotive Behavioral Therapy. REBT, while very powerful, is an approach we find more complex and therefore more difficult to teach and practice. For that reason we emphasize the older and, in our opinion, simpler RET which can be taught in minutes, is easily remembered, and amazingly easy to use. We also see RET is a major method for developing mindful awareness of how we disturb ourselves.

In recent years we have embraced Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), and with a little tweaking of the RET model our version of RET is made consistent with ACT. We will discuss ACT later in this chapter. First, however, we will talk about RET with our own variations that we have found useful over the past several decades.

RET is best used whenever something has happened that is particularly distressing, shameful, or that produces strong emotions such as rage, guilt, fear, or despair. It's ideal when one is left with feelings of hopelessness, helplessness, and worthlessness, or when you find yourself awfulizing and catastrophizing. It's definitely of great use when you're feeling depressed or anxious.

RET is not meant to get rid of all disturbing feelings as some emotions are entirely appropriate. For example, if you have been mistreated, taken advantage of, or abused, anger is a perfectly legitimate emotion and needs to be expressed effectively rather than rationalized away. The worst things you can do with anger are denying it, avoiding it, stuffing it, or being so frightened that expressing anger is hurtful, makes you a bad person, or certain to evoke painful retaliation, that you do nothing.

RET is for those situations where you are clearly disturbing yourself needlessly, and producing emotions that are not only very troublesome, but unnecessary. It's for those situations where you are disturbing yourself.

RET is usually done retrospectively on paper, although with practice, you will find yourself doing it in your head as events are occurring. Try to use paper wherever possible as writing things down allows you to be more complete and to remember more fully and accurately. Also, there is kinesthetic learning. The act of writing more effectively gets new learning into your memory files.

All you have to remember to use RET are the letters A, B., C., D., and E. What could be simpler? On a piece of paper, vertically list of these letters in the left margin covering the length of the page and leaving extra space at B and D.

Start with C which stands for the emotional consequences of something happening, or "feelings" for short. Following an unpleasant event, list all the emotions you are aware of at C. Push yourself to get a complete list of emotions you’re noticing.

The reason we start with feelings is that you are most aware of unpleasant emotions, and may not be aware at all of disturbing automatic thoughts. Often our clients claim that they are feeling very uncomfortable emotions but not really thinking anything. You can be quite sure however that disturbing thoughts, or at least disturbing images, are there but they may be occurring with lightning speed and beyond awareness until you slow things down and become "mindful" of what's going on "in the now."

Following listing all the feelings you are aware of, go back to A which stands for "activating event" or "antecedent event" (it works either way). It could also stand for “adversity.” A is the "situation," you are responding to. Write only a phrase or short sentence to describe what has triggered strong emotions. Ask yourself if this situation automatically leads to the heavy feelings you have listed at C. Ask yourself if other people would respond in exactly the same way, with exactly the same feelings. The answer is most likely "No." They might have similar strong feelings but those feelings will not be exactly the same as yours. Clearly you are doing something else that is unique to you in producing the feelings you experience. The "something else" can be found at B which stands for your "beliefs," or self-talk.

At B, list all of the things you are telling yourself in response to A, in turn producing the feelings at C. Push yourself to uncover disturbing thoughts that match the strong feelings you have listed. For example, if one of your feelings was despair, you must be telling yourself something quite disturbing such as "I'll never get any better. My situation is truly hopeless."

Possibly the greatest problem people encounter in doing RET, is not going far enough in uncovering inaccurate, irrational, and disturbing thoughts at B. Push to go as far as you can. Look at each statement and ask yourself -- "Okay, if I believe that, it therefore means ..." Continue until you have uncovered your most extreme negative thoughts. Don't shortchange yourself on the step. Don't cut corners. Don't try to do it all in your head – at least not until you have had a lot of practice with this technique. The extra work will pay off with major dividends in changing your self-talk.

Next go to D which stands for "dispute." For each of the thoughts you have uncovered, ask yourself "How do I know this is true? What is my evidence? Looking at my own life or other people's lives, is there evidence to the contrary? Is this thought or belief supported by what I know to be true? Is there an alternative view that would make more sense? Is there another way of looking at this situation that has real evidence to support it?"

Note that D is where RET becomes inconsistent with ACT. Proponents of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy maintain that it’s unnecessary and even counterproductive to get caught up in determining whether or not the self-talk is true. Instead, an ACT practitioner would consider A,B. and C as simply noticing what your mind is telling you, with D more properly being ”defusion,” or detaching from over- identification with, or “fusion” with the thought or belief.

We ask our clients to first practice RET as presented here. We see it as a process for becoming very mindful of your most frequent irrational thoughts and beliefs. More about ACT will be presented following the RET discussion.

As you become more aware of your thinking and more skillful at successfully disputing disturbing thoughts or beliefs, your emotions change. At E you list new "emotional effects." If you've done the preceding work well you will notice the feelings have changed significantly. Instead of despair, you might be experiencing optimism. Instead of fear, you may have found new courage to deal with a situation that needs to be dealt with. Instead of emotions that are so disturbing that they result in over-eating, under-eating, alcohol abuse, panic attacks, or a fight or flight response to conflict, there may be new opportunities for dealing with situations in powerful and positive ways, and in ways that build confidence and self-esteem.

How about an example? This comes from something that happened to Bill over 35 years ago, something that has frequently provided a useful example of how RET works. The following is the account of the RET situation in Bill's words:

I was scheduled to give a talk to a college class on Rational Emotive Behavioral Therapy. I needed approximately 30 min. to get from my office to the classroom. The class was to start at 5:30 PM and my intention was to leave shortly before 5 PM. Just prior to leaving, the phone rang. On the other end of the phone was a very distraught, seemingly out of control, client apparently in major crisis. I had to take the time to make sure that she was not a danger to herself, that she had someone with her for her own safety, and that she would be available to come in for a session the next morning. This took time, and by the time I hung up the phone, it was 5:10 PM. Okay, I would be late but hopefully not too late to give my talk. I sprinted to my car, quickly got on the freeway, and encountered – gridlock!

No problem! I exited the freeway and got on surface streets only to find myself in one of those situations that we all hate. I was about the 14th car in the left turn lane at what had to be the slowest traffic light on the planet. Two or three cars would turn left with the green arrow before the light once again turned red for what seemed like an eternity. It was very late and getting later. To top it off, on one of the hottest days of the year, my air conditioner suddenly quit. I was dressed in a coat and tie and felt like I was melting. Feeling intensely uncomfortable physically, I became aware of a rising tide of emotion, specifically anger, embarrassment, frustration, and high anxiety.

I decided there would never be a better opportunity to practice RET. Starting with identifying the feelings above (Step C of A-B-C-D-E., I next linked to the activating event or situation at A. In a nutshell, I was going to be very late.

The next step was identifying "beliefs" at B. What was I telling myself? The self-talk had to be sufficient to bring about strong feelings such as anger, embarrassment, frustration, and high anxiety.

I decided I had been telling myself:

- I am not a late person, and it's unprofessional to be late.

- I can't stand being late.

- My students will judge me negatively.

- This traffic light should be faster.

- These cars should not be in my way.

- My car air conditioner should be working.

- This is a terrible situation, in fact 150% terrible, and I can't stand it.

I next tackled D (for "Dispute"). This one was easy, especially since the last four items above were totally irrational. I began by reminding myself of the Serenity Prayer:

God grant me the serenity

to accept the things I cannot change;

courage to change the things I can;

and wisdom to know the difference.

Living one day at a time;

Enjoying one moment at a time;

Accepting hardships as the pathway to peace;

--Reinhold Niebuhr

Let's get back to my awareness of the things I was telling myself. The last four thoughts were clearly irrational as I was railing against things totally beyond my control. Consider: “This traffic light should be faster.” What could be more irrational than getting angry at a machine? The first four items were equally unreasonable and based upon faulty evidence.

Each thought was quickly tested by asking myself: "How do I know that's true? What's my evidence? Is it real evidence or is it rather flimsy? Is there evidence to support an alternative view? What could I tell myself that would make more sense and serve me better in this situation?

Alternative thoughts that were far more sensible included: Sometimes being late is unavoidable. Being late is better than getting in an accident or having a heart attack. My students will understand. Anyway, I've been a student for most of my life and students rarely resent it when an instructor is late. They usually enjoy having extra free time. I have no control over my air conditioner, the traffic light or the traffic, and these other folks are in the same situation that I'm in through no fault of their own. I’ll get there when I get there, and whatever happens, I'm still okay with me.

At that point my feelings changed to relief and optimism (E). I loosened my tie, slipped off my jacket, turned on a mellow FM station, reminded myself to breathe diaphragmatically, relaxed my body and proceeded to my class.

My students were still there having enjoyed time to socialize. I had a great class and never got the headache I might've gotten in past years. I used my traffic example and my students got it! It was a very successful class. Without experience and practice in doing REBT my evening would have gone very differently.

How long did it take from my air conditioner quitting to turning on the FM station? It took less than a minute and was probably closer to 30 seconds.

That's the beauty of practicing RET. Disturbing thoughts flow through your mind with lightning speed and just as quickly you can sort them out and choose thoughts that are more realistic and less anxiety producing. The key ingredient once again is PRACTICE! If you take a pencil and paper and regularly go through the RET exercise whenever you find yourself emotionally upset, you'll find you soon develop the ability to quickly catch yourself in the act of disturbing yourself, and just as quickly shift to treating yourself with more acceptance, patience, and compassion. You will find yourself dealing with the same dozen nutty thoughts, over and over again, until you have become instantly mindful of the thought as it’s occurring. That's the real payoff! You catch yourself in the act of disturbing yourself and instead defuse the thought, seeing it as only a thought and not something you have to obey.

With practice, it gets easier and easier to have self-awareness in the moment. You discover that whenever you become aware of feeling stressed or anxious, you can quickly connect with yourself by taking a full diaphragmatic breath and checking in with your cognitive self. The following questions may be helpful:

- What am I telling myself about my coping ability? What do I perceive to be a threat?

- What am I feeling? What are my emotions?

- What's going on in my body? What is my physical experience?

- What am I telling myself that is not accepting or compassionate?

- Are there things I can't control? Are there things I can control?

- Could I be more accepting and compassionate toward myself? What would I be telling myself if I were more compassionate?

- Do I have needs that are not being met? Do I have boundaries that are not being observed, or asserted?

- Am I being realistic? Am I engaging in "what if thinking," or "awfulizing" or “catastrophizing?"

- What are my choices? What options am I aware of when I do view my situation from a position of calmness and self-acceptance?

Let's check in with Matt again as he anticipates a possibly contentious evening with Beverly.

When we left Matt he had just arrived home and already there was tension between he and Beverly. Feeling anxious and angry he hastily changed clothes and headed downstairs to help Beverly get dinner ready.

Beverly's mood had softened and she smiled as he entered the kitchen. "I'm sorry I jumped on you as you walk through the door. It's just that I get so frustrated when there is so much to do and so little time. Can we switch gears and have a good evening?" Matt nodded in agreement and gave her a heartfelt hug and kiss. "Glad to be home," he said. "Yeah, let's make it a good evening."

The crisis was over. The difficulty had only lasted 15 minutes.

Matt felt relief but also frustration. Why do I keep doing this to myself? There’s good stuff in our relationship, and a lot of it. I can’t complain, but then I can’t really enjoy being a couple either. I keep stressing about all the things that might go wrong, or beating myself up over past mistakes. Why can’t I just relax, be in the moment, and for just this moment, let things go?

Matt recalled a quotation from Mark Twain. He thought it was funny when he first heard it but now he was realizing the truth of it in his own life.

“I am an old man and have known a great many troubles, but most of them never happened.”

Two days later Matt recounted the situation for his therapist: “I was on the verge of a panic attack. I just knew I would be in trouble even though I couldn’t think of a valid reason for being so stressed. I just keep doing it – creating upsets in my own mind. I’d just like to be able to let go of stuff and relax.

His therapist replied: “When you say you just keep doing it, you’re talking about being on autopilot. It’s a knee-jerk pre-programmed reaction whenever you’re in a similar situation. It’s actually a well-practiced and deeply entrenched cognitive-emotional-behavioral habit and it’s taking place before you’re fully aware of any thought processes at all. What’s needed is the ability to slow things down, be mindfully aware in the moment of what’s taking place, then choosing a direction that makes sense. I’m reminded of one of my favorite quotes. Psychologist Rollo May said:

Real freedom is the ability to pause between stimulus and response, and in that pause to choose.’

“Even though he may not have known the term at the time, May was talking about mindfulness and the ability to be so aware in the moment that you can actually create some space between the situation and your response, being able therefore to purposely plug-in a reality-based emotionally intelligent response.”

Matt had been listening, but couldn’t wait any longer to ask: “Okay, I get it that I need to be able to slow down, process things differently and make better choices. So how do I do that?”

The therapist replied: “First, you can learn and practice a systematic method for becoming aware of negative self- talk. Each of us has our own dozen nutty thoughts, and you become so aware of your dozen that you catch yourself when an unhelpful thought pops into your head. We use a combination of two methods to bring about mindful awareness and the ability to ‘defuse’ unhelpful thoughts. The first process is called Rational Emotive Therapy, a cognitive behavioral approach that we’ve modified to blend with a second powerful set of tools – Acceptance and Commitment Therapy.”

The therapist proceeded to explain how we use Rational Emotive Therapy. “After something has happened such as coming home to Beverly, take out a sheet of paper and begin to fill in A, B, C, D, and E. let’s use the situation with Beverly as an example. We’ll start with C, the emotional consequences or feelings and the physical sensations that came with the emotions. What were your emotions and physical sensations as you were walking from the front door to the kitchen?”

“Let me see,” Matt said as he reflected on the question. “Certainly I was feeling a lot of anxiety and fear, even to the point of feeling panicky. I was dreading an encounter with Beverly and had a strong urge to avoid the whole thing. I know it’s not an emotion but I was reacting physically, breathing hard, feeling a tightness in my chest and around my forehead. I was sweating profusely, and I was even a little lightheaded. Along with the dread I was feeling confused, having a tough time thinking straight.”

“This is a great start,” said his therapist as she filled in the RET sheet. “You were feeling anxiety, fear, dread, and confusion. Backtracking to A, the situation, it was simply anticipating talking to Beverly. Would you say that such a situation automatically generates such strong feelings? Would everyone else have the same kind of feelings? Of course not, but you did in this situation so something else was happening, and that something else can be found at B, your learned beliefs or self-talk. What do you suppose you were telling yourself as you entered the house?”

“I was searching my memory banks,” said Matt. “I was asking myself if I’d missed something that would upset Beverly. I was trying to think of something I’d screwed up. I was telling myself I was in trouble being late. I instantaneously moved from that thought to telling myself my marriage was in jeopardy. I imagined an arguement. I worked myself up into quite a state, and this was only coming from my car and walking through the front door.”

“You seem to do a lot of ‘what if’ thinking when something unexpected happens or when you don’t have control over the situation. Is that accurate? The therapist already knew the answer.

“Yes, absolutely,” replied Matt. “I can ‘what if’ myself to death. There is no end to it and I make myself sick.”

His therapist proceeded to take Matt through D, the dispute section of the RET sheet. There was plenty of evidence Matt was secure in his jmarriage. There was no rational reason for him to worry excessively. His “what if” thinking was a habitual reaction that could be traced back to his childhood. Learned negative self-talk left him perpetually anxious and insecure, and greatly impacted his quality of life and that of those closest to him as well.

His therapist continued: “As we look at the situation from a more realistic perspective, you can readily see alternatives that are better supported by the evidence. What might you tell yourself that would make more sense?”

“Well, now that I’m thinking more clearly, and I’m calmer about the whole thing, I can tell myself that I we love one another and we’re both solidly committed to the marriage. Also, there’s lots of evidence I’m appreciated for what I do. The Mark Twain quote really hits home. I worry needlessly.”

“And what are the feelings you’re left with?” The therapist was moving on to E, New Emotional Effects.

Matt responded immediately: “Well, the anxiety is gone. I’m feeling optimism and also rather secure in my relationship This was very helpful. I’m not only seeing things differently, but it feels good.”

“Great!” The therapist proceeded to congratulate Matt on the work he was doing, but also to help him understand that old habits die hard, and that it would take repeated practice to rewire his brain.

“What I’m suggesting Matt, is that you do an RET sheet each time you’ve found yourself in a similar situation. Over time you will become so aware that you will catch yourself in the act, and instantaneously choose a different course of action – a different way of thinking, feeling, and behaving. With this kind of practice, you have the power to literally rewire your brain, finally moving beyond an old habitual way of thinking and reacting.”

“With growing awareness of how you disturb yourself, and when you start ‘catching yourself in the act, ’ you need to move from RET to ACT, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy.” It will no longer be necessary to do an RET sheet for a ‘nutty” thoughts. All you will need to do is be aware, notice the thought, and tell yourself: ‘I’m noticing my brain is once again generating my old what if thinking. That’s not very useful to me and it doesn’t fit in with what I want. I accept that the thought pops into my head, but I’m not going to get caught up in it or be controlled by it. I’m going to keep on moving toward my goals and choose to remain positive.’ I don’t really have control over my brain generating the thought, but I can mindfully be aware and accepting of the thought, choosing to do what’s best for me anyway.”

Matt was definitely onboard. “I can clearly see how this works. It’s working already! “Good,” the therapist replied. Bring some RET sheets with you next time and we will keep this process going.”

ACCEPTANCE AND COMMITMENT THERAPY (ACT)

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, or ACT, is a powerful change modality based on two principles: mindfulness and values. The purpose of ACT is the effective handling of painful thoughts and feelings while creating a rich, full, and meaningful life. Three essential skills are central to the awareness and openness of being mindful. 1. Defusion is being able to detach or unhook yourself from disturbing thoughts and self-limiting beliefs so these qualities lose their power to control your life. 2. Expansion means making room for unpleasant thoughts and feelings so they simply flow through you rather than sweeping you away. 3. Connection means being fully present in the here and now, rather than being preoccupied with the past or anxiously focusing on the future. ACT is about connecting with your values and finding meaning, purpose and direction in life through values-based committed action.

The ABC steps of Rational Emotive Therapy are very consistent with ACT. The ACT philosophy is that our thoughts consist of words making up stories. When we get so caught up in negative stories that we fuse with them, we become cut off or disconnected from the things that we value and the things that make life meaningful. In both RET and ACT, holding on to negative thoughts and beliefs to the point that you believe them, think you have to give them your full attention, have to obey them, do what they suggest, or simply react to them as dangerous and frightening, leads to disturbing yourself unnecessarily. Russ Harris, author of The Happiness Trap, refers to this as “dirty pain.” We refer to it as “elective suffering,” suffering that is self-inflicted, serving no useful purpose.

Working the ABC steps of Rational Emotive Therapy can make you more aware of thoughts, beliefs and images that are disturbing. RET maintains that you disturb yourself by buying into, or uncritically accepting, negative self-talk, and self-defeating beliefs. In ACT language, the problem is “fusing” with the stories you are telling yourself. It’s much the same thing with both approaches, and our view is that working the first three steps of RET can help you become more aware, and better able to do the work of ACT.

The difference occurs with the RET emphasis on disputing (D) negative self-talk, checking facts, correcting mental errors, debating the validity of the story, and creating a better story. ACT maintains that this is not useful, and focuses instead on defusion. According to ACT, practitioners, it’s not particularly important whether or not a thought is true, but instead asking yourself whether or not it’s helpful to hold onto it, and whether or not it supports you pursuing and living your values.

Defusion means seeing thoughts as simply words and unhooking yourself from having to react to them. Instead, you can pursue what matters most, engaging fully in living a values-based life. It’s not necessary to struggle with disturbing thoughts and painful feelings. This just makes them stronger. Instead, ACT practitioners utilize their “observing self,” stepping back and noticing thoughts, created by the “thinking self.” While being in your observing self, you can choose to let thoughts come and go, aware of when you are fused with the thought, then proceeding to unhooking from the thought and refocusing on moving toward your values. It’s important to let go of judgment or expectations, simply accepting what comes. You may have to “unhook” yourself many times, but that’s how you become skillful at defusion. Simply step back and say to yourself: “I’m noticing that my mind is telling me…” Make space for the thought and choose to commit to doing the things you need to do anyway.

ACT is a fascinating approach and takes traditional cognitive behavioral therapy to a whole new level. Several very fine ACT books are found in our reading list at the end of this chapter. Meanwhile, let’s take a closer look at distorted thinking and self-talk. An awareness of how we humans can’t help but deny, distort, and falsify reality, enhances both traditional cognitive behavioral practices such as RET, as well as Acceptance and Commitment Therapy.

Distorted Thinking and Self-Talk

Maintaining an anxiously insecure attachment style or an avoidantly insecure attachment style (pursuer or withdrawer) requires distorted thinking and negative self-talk. Distorted thinking is the basis of our preoccupation with fearful things that might happen in the future, or things we regret having happened in the past, along with the fear, anger, and reactivity that keeps us stuck

The following are specific styles of distorted thinking that apply to many with anxiety, depression severe stress, or problematic approaches to relationship challenges. Each description is followed by examples to illustrate how highly stressed or anxious people might unconsciously utilize that style as a way of protecting themselves, while in reality maintaining and deepening their distress. Note that these distortions overlap and usually occur in teams.

Personalization

When you personalize, you tend to relate things happening around you to yourself in a most negative way. A central aspect of personalization is the habit of continuously comparing yourself to other people, always believing you don’t quite measure up.

The opportunity for comparison with others is limitless. A basic assumption for personalization is that you have worth only if you compare well with others, and your worth is therefore tentative, temporary, and questionable. Personalization means continuously testing your worth as a person by measuring yourself against others. If you meet someone with major flaws, you may experience brief relief; however, this is not often the case. Personalization usually means that you find ample evidence of your flaws. You therefore feel diminished, inadequate, and not quite good enough.

Personalization also means that you interpret each experience, each conversation, each glance from another as hard evidence of your inherent unworthiness.

Betty felt extremely uncomfortable in her first Anxiety and Stress Management group meeting. She was quite sure even before she arrived that each of the other participants would be handling their anxiety better. Additionally, she was expecting they would be more intelligent and successful. It never crossed her mind that because it was a stress and anxiety group that the others had similar problems. Upon sitting down in group, she was filled with fear. In her mind, she excelled in being out of control and debilitated. Her perception was that each of the other members was more together and, more capable at meeting their needs. Certainly they must be showing rapid improvement. Their normal curiosity about a new group member was perceived by Betty to be a clear indication that they were thinking critical thoughts about her. When several group members talked among themselves prior to the start of group, Sally was convinced they had to be talking about her. Only with additional group time, the sharing of other group members, and their obvious friendliness toward her, did Betty begin to relax. When the group expressed insecurities similar to her own, Betty was shocked. Could it be possible that others felt the same way? It would take many more group sessions before Betty realized fully how her perceptions were distorted. In reality, she was accomplished and talented. Her intelligence was above average. Personalization, however, virtually always leaves an individual feeling inadequate and depressed.

Overgeneralization

This is a distortion that leads you to take a small piece of evidence or a single event and make a sweeping generalization that colors your entire life. Overgeneralizations are usually thoughts in the form of absolute statements, such as “always” or “never.” These are distortions that almost always lead to an increasingly restricted life and a gloomier view of self.

Whenever you conclude that “Nobody loves me” or “I’m never going to recover,” you are over- generalizing. Usually your conclusion is based upon some small piece of evidence and involves turning your back on everything you might have heard to the contrary.

Jane is always on guard. She tenaciously clings to the belief that her next mistake will be her ultimate undoing. There’s simply no margin for error and she’s waiting for that one big screwup that will cascade into a never ending descent into oblivion. To Jane, one small leak in her boat means the boat will surely sink and she will drown. Consequently, Jane leads a more and more restricted life, clinging to the familiar and avoiding risks. Of course, this avoidance inevitably leads to boredom, loneliness, and the extreme stress of unmet needs. All Jane can think of are past failures and her conviction that the future only holds more of the same. Catastrophizing and awfulizing , and being hypervigilant are the dominant themes of her life.

Generalization means that you carefully ignore everything you know about yourself that is contrary to the sweeping conclusion you have drawn from one or two pieces of evidence. Key all-or-nothing words that go along with overgeneralization are all, every, no one, never, always, everybody, and nobody.

Catastrophizing

We are reminded of a Woody Allen movie in which his headache was certain evidence he had brain cancer. Catastrophizing means that whenever bad things can happen, surely they will occur. For stressed out and anxiety disordered people, it means that if it is possible for things to get progressively worse, surely they will. If it is possible to be an anxiety "basket-case," then of course that outcome is a certainty.

Catastrophizing self-talk often starts with the words “what if.” What if this happened or that happened? If it can, then it will. The list of possible calamities is endless. Anxiety disordered individuals are worriers. In particular, they worry about being out of control and never getting better. There is also a lot of worry about having serious medical problems. Since these things are possible, they are already guaranteed to happen.

George has struggled with his anxiety for years. He has had frequent trips to emergency rooms resulting in a multitude of medical tests. No medical basis has been found to explain his symptoms but for George, this only means that his doctors have missed it, whatever "it" is. The panicky feelings he experiences during an anxiety attack have been so unpleasant that he's convinced there must be some terrible physical problem. He's fearful of dying, or losing his mind. He’s certain that his rapid heart rate when he's stressed means he's about to have a heart attack. Meanwhile, George seems unaware that there are real issues in his life that he has ignored. His search for the "real" problem continues.

Polarized Thinking (also known as Dichotomous Thinking)

The central theme of this distortion is the belief that the world consists of black or white choices. Things have to be either one way or the other. There is very little room for middle ground. People and things are good or bad, wonderful or horrible, successful or miserable failures. Polarized thinking leads to an either/or world where reactions to events swing from one emotional extreme to its opposite. Perhaps the worst problem with polarized thinking is the effect upon self-image and self-esteem. If you are not perfect or wonderful in every respect, then you are surely reprehensible, a “worm” of a person beneath contempt. There is no room for mistakes. Each new day brings with it a thousand more tests, and anything other than a perfect score is ultimate failure.

Louise weighs herself incessantly. Like many people with food and weight problems, Louise thinks if she is not perfectly thin, she must be terribly fat. If she is not totally in control of her food, then she is absolutely out of control. Food is either good or it is bad. The bad food is to be avoided at all costs. One small slip, one small bite of the bad food, means that you, the dieter, have gone from being a good, in control dieter to a horrible out-of-control foodaholic. Of course, Louise does not see the connection between over-control and being out-of-control. She does not realize that this extreme restraint and polarized thinking leads her to abandon all control once she perceives perfect control is no longer hers. This means any attempt to modify her food and weight behaviors ends with the first deviation, the first small slip. To Louise, any change from her plan is total failure. Either the plan runs perfectly smooth or it is a disaster and readily abandoned, and Louise has once again proven herself unworthy. Each Monday Louise begins a new diet. By midweek, she has abandoned the diet and the incredible self-restraint that goes with it. She once again promises: “Monday I will begin again.” Meanwhile, Louise perceives herself as weak and ineffectual, someone who has no will power. After all, you either have it or you don’t.