Chapter 17: The Dialogue Option: Respectful, Empathic, and Transformational

CHOICE 8. THE DIALOGUE OPTION: RESPECTFUL, EMPATHIC, AND TRANSFORMATIONAL

In true dialogue, both sides are willing to change.

Thich Nhat Hanh

Speak when you are angry and you will make the best speech you will ever regret.

Ambrose Bierce

The single biggest problem in communication is the illusion that it has taken place.

George Bernard Shaw

Genuine dialogue, not rhetorical bomb-throwing, leads to progress.

Mark Udall

OUR EVOLUTIONARY DISADVAVTAGE

The Zeigarnik Effect

In the 1920s Lithuanian psychologist Bluma Zeigarnik found that the completion of a task can lead to it being forgotten, while incomplete tasks, particularly those unfinished tasks that are frequently revisited, are recalled in great detail. This has great relevance for couples.

According to Julie Gottman, co-author of 10 Principles for Doing Effective Couples Therapy: "If a couple hasn't fully processed a searing incident between them, they can't let it go. But once they discuss it and grasp the mistakes they've made, their meanings and teachings, the incident can finally be laid to rest."

Often the past is not really past. As therapists we have no interest in endlessly processing things that neither partner is hanging onto, but those issues that are still being debated or fought over, aren't past. They are very much in the present and must be fully processed before partners can let go and move on in co-creating a desirable future.

The photo was taken off the coast of South Africa, well known for Great White sharks frequently photographed feeding on seals. In this particular photo a Great White has come barreling up from the depths, mouth wide open, fully anticipating its next meal, the seemingly unaware seal on the surface. However, seals are extremely agile and this particular seal spring-boarded off the shark’s nose and was well out of range by the time the shark closed its mouth and realized its next meal was already somewhere else.

However, our focus is not on the shark but on the seal.

Robert M Sapolsky is a professor of biology and neurology at Stanford University and the author of several works of nonfiction including: "Why Zebras Don't Get Ulcers." His research on the stress response in animals has done much to help us understand how we differ from other animals in our response to situations we perceive as dangerous.

Unlike other animals, we're great at remembering bad stuff and anticipating bad stuff, endlessly obsessing about both past bad stuff and future bad stuff.

Perhaps this reminds you of your couple relationship? Do bad memories of past encounters plague you? Do you fear relationship events that haven’t happened yet?

The seal, like other animals, and us humans, will be flooded with adrenaline during a moment when survival is on the line. However, there is a crucial difference in how seals and other non-human animals recover.

Seals are very smart and incredibly well adapted to their environment. Part of that adaptation is an amazing ability to have their physiology return entirely to normal just moments after escaping a near-death experience with a Great White shark. A quick return to a non-emergency state allows the seal to go about its business without any disruption – until the next Great White appears.

We humans are quite different, and you can blame it on our oversized brains. You have ability to remember in great detail every bad thing that ever happened to you, every rotten thing told you by someone close, every betrayal, every wounding, every difficult encounter. Moreover, you have the ability to endlessly ruminate on negative events from your past.

Of course, this ability has survival value. If you burned your fingers on a hot pot, you know to use potholders in the future. If your ancestor ate something that made him or her extremely ill, they forever avoided whatever it was and cautioning everyone else to do the same.

There is a huge inherent interpersonal problem with your ability to remember and dwell upon negative events of your past, perhaps a past injustice or wounding inflicted upon you by your partner. You can't let it go until it's been fully processed. The anger and resentment will keep bubbling up and getting in the way of the closeness you so much desire.

On the other hand, you may personalize past conflict situations and beat yourself up for having been in that situation or handled it the way you did. The result is avoidance, shame, guilt, and/or depression, — qualities that often undermine and even destroy a couple relationship.

Having a future means letting go of the past and the best way we know of resolving past issues and moving on is dialogue.

"The past is never dead. It's not even past."

William Faulkner

And then there is the future.

Unlike the seal, you have the uniquely human ability to worry endlessly about things that haven't yet happened. Are you sometimes anxious about the future? Are you anxious about the survival of your relationship? Most people sometimes worry about their relationship and fully 40 million of us have a full-fledged anxiety disorder.

The people we see in couples therapy almost always have significant anxiety about their relationship, and their level of anxiety may range from moderate to full-blown panic. Almost all have "anticipatory anxiety," and engage in "what if?" thinking, imagining all kinds of unpleasant things happening in the future. How about you?

Mark Twain said: "I am an old man and have known a great many troubles, but most of them have never happened."

How do these distinctly human qualities affect couple success?

There's not much success in couple relationships in terms of actually growing old with the same partner, and much of that stems from the very qualities that helped us survive as a species. We have exquisitely clear memories of past unpleasantness, particularly past threats to our well-being. This certainly applies to almost all couple relationships.

We hang on tenaciously to previous injustices,, disappointments, abuses and emotional woundings. We get triggered and respond with emotions and behaviors from our past (See our discussion of schema in Chapter 2). The resulting behaviors are maladaptive and don't work any better than they did in our past, but we are programmed to repeat them in what Sigmund Freud called "repetition compulsion."

We often have our guard up, anticipating new pain, new distress, new wounding, new betrayals. As expressed by Mark Twain, we anticipate troubles that may never happen, but we guard ourselves nonetheless. How about you?

It may be that we are more wired for war than we are for love. Our brains lead us to constantly scan our environment for danger while tenaciously holding on to memories of past dangers.

You may recall our discussion of "Ladders of Inference" in Chapter 2. We make assumptions based largely on past experience as we make our way step-by-step up our ladders, often concluding with unjustified judgements and beliefs about our partners. We add meaning, make assumptions, and often leap to conclusions poorly supported by real evidence. We may see our partner as dangerous, and not to be trusted, stuck in the past, fearful of the future.

Almost all of us find ourselves up our ladders of inference on occasion. How about you?

No, you’re not about to be eaten by a Great White, but your brain may lead you to see your partner in such a way that alarm bells are sounding and your choices seem limited to fight, flight, or freeze. How often have you found yourself emotionally triggered, with a knee-jerk automatic response you later regretted?

What then is the solution if your highly evolved brain, still possessed of primitive survival structures, is not only programmed for connection but also powerfully programmed for both defense and offense. Your primitive response to threat often leads you into great difficulty with the one you need the most. Someone you cherish can suddenly appear as a Great White.

You need secure emotional attachment like you need oxygen, but you also need safety and a solid defense against perceived threats. A dilemma! What do you choose?

The answer is something that doesn't come naturally. It may seem unnatural to you to give up control, give up having to be right, give up having to win, give up having to fix it, give up defensiveness, instead opening up to your partner and choosing to be vulnerable. Vulnerability involves risk and trust. It often feels unsafe— and doesn't come easily for most people. This definitely involves mindful choices and self-calming skill, not behavior that is highly compatible with a more primitive protective brain that is wired for defense and survival.

THE CASE FOR DIALOGUE— A MOST UNNATURAL WAY TO COMMUNICATE

Imagine quite naturally listening attentively, not reactively, to your partner. Imagine describing your feelings rather than attacking with them. Imagine having great emotion regulation skill, along with the ability to effectively co-regulate emotion with your partner. Imagine being able to pursue understanding rather than agreement, and skillfully engage your partner in conversations that matter, where you both have strong feelings, and where you have very different opinions.

Unfortunately, most couples have difficulty managing their differences and disagreements. One solution is mastering a skill that doesn't come naturally, and that skill is "dialogue."

Dialogue is the free flow of information between partners. It's not withdrawing, defending, blaming, or attacking. It's not being passive and it's not being aggressive. It’s not critical or judgemental.

That's what dialogue isn't. Shortly we'll go into detail as to what dialogue is. First however, why is dialogue necessary and why is it so important in a couple relationship?

A conversation with your partner is a conversation between two unique individuals who each bring their own opinions, emotions, beliefs, memories and experiences about the topic. It's highly likely that partners will frequently see things differently and this difference may lead to conflict

The following is our definition of conflict:

An inevitable quality that results whenever two or more individuals, each having their own history, perceptions, values, needs, wants, goals, and styles of relating, experience elements of incompatibility and are each faced with choices on how to respond.

Notice that we've highlighted "inevitable" and "choices." The two of you can't possibly agree on everything, and conflict (overtly expressed or suppressed and hidden) is inevitable. When you do find yourself in conflict, you have choices on how to respond, even though those choices are sometimes obscured by strong emotions, unresolved past issues, fearfulness about the future, and autopilot “knee-jerk” responses.

These inevitable areas of conflict have been referred to as "crucial conversations," in the book by the same name. Crucial Conversations authors Patterson, Grenny, McMillan, and Switzler state:

"When stakes are high, opinions vary, and emotions start to run strong, casual conversations transform into crucial ones. Ironically, the more crucial the conversation, the less likely we are to handle it well."

Not all conversation require special handling. Sometimes you and your partner are engaged in small-talk, just catching each other up on the news of the day. Sometimes you're simply imparting information or making a request such as: "It's Thursday. Don't forget to take out the trash." Sometimes your commenting on the weather. Most conversation is lighthearted, nonserious, casual and easy.

Then there are the conversations that DO require special handling, conversations

that are perceived as very important, where the two of you do not agree, and where strong emotions are present. Often there is a perception that much is on the line with consequences of not agreeing being severe.

Benjamin Franklin said: "All progress comes from disagreement." We think this is certainly true for couples. Your relationship cannot grow, cannot become deeper and more satisfying without openly dealing with disagreement.

You might be thinking: "Wait a minute, disagreement can also destroy a relationship."

Yes, that's possibly true but it all depends upon how disagreement and conflict is dealt with.

Having to win, be right, or even inflict emotional pain on your partner is of course destructive. Also, avoiding conflict or not being candid about your true needs and feelings can be equally destructive.

Partners often tell themselves:

- Conflict is awful

- My needs are more valid than yours

- Only one of us can win

- My viewpoint is correct, and based upon "real" evidence

Dialogue is based upon very different beliefs and very different self-talk. Dialogue requires the positive expression of emotion, and the ability to discern the emotions behind your partner's words without being threatened, flooded by your own strong emotion, or caught up and self- protection.

Negative self-talk about emotions often gets in the way of dialogue. Can you describe your emotions rather than attacking with them? Can you listen to your partners complaints without being defensive? Can you respond to your partners anger or hurt without focusing inward on your own protective reaction? Can you check yourself when you're about to be flooded with strong emotion and instead turn your focus toward listening, accepting, respecting, and validating? Can you manage your emotions without your emotions managing you?

Are you uncomfortable with strong emotions, or emotions you perceive as "negative?" The following are examples of common judgements and negative self-talk about emotion:

- Emotions are bad or just plain dumb

- My emotions aren't important

- Others don't care about my feelings, so I shouldn't care either

- Expressing my feelings is a sign of weakness

- Being emotional is the same as being out-of-control

- Anger is not for women

- Fear is not for men

- I should never feel afraid

- Anger is to be avoided

- Being emotional is a sign that I'm weak

- Emotions always get in the way

- Emotions are for the hysterical

- I wish I never felt anything

- There is never a right time for strong emotion

- I'm afraid of my emotions

- Anger is hurtful and destructive

- Anger and love are incompatible

Sometimes there are hidden agendas such as:

- I’m good and you’re being unfair

- I’m good (but you’re not)

- You’re good (but I’m not)

- I’m helpless, I suffer

- I’m innocent and blameless

- I’m fragile

It definitely helps if you have the ability to calm down, slow down, give up control, give up having to be right, and instead embrace the following assumptions:

- Conflict is inevitable

- Our goals are equally valid

- We don't have to agree but we do need to understand each other

- We can both win

- Conflict is usually an opportunity to grow and strengthen our relationship

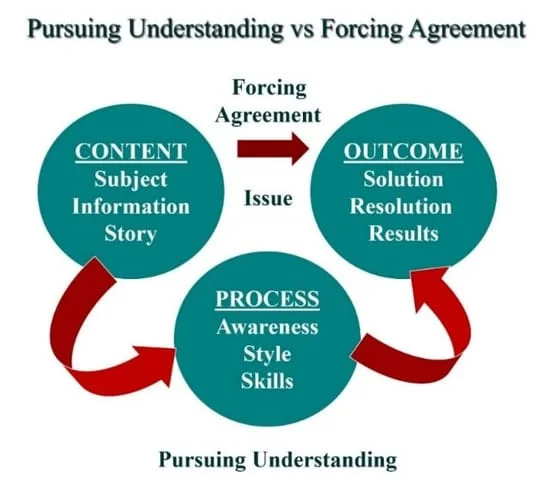

Conflict is an opportunity? The opportunity comes with pursuing understanding rather than agreement, and focusing on process rather than content.

Figure 17-2: Focus on Process

Getting really charged up with strong emotion and trying to force agreement to get the outcome you desire generally doesn't work. The more you push for agreement, the more opposition you will get. If your partner feels attacked or doesn't feel safe, he or she will either shut down or fight back. Either way, you're not going to get a stronger and healthier connection.

On the other hand, if you can slow down, calm down, and focus on the process, it's more probable that you your partner will achieve a positive outcome. In other words, if you can focus on how the two of you are communicating and strive for communication that is safe and mutually respectful, you're going to get better results.

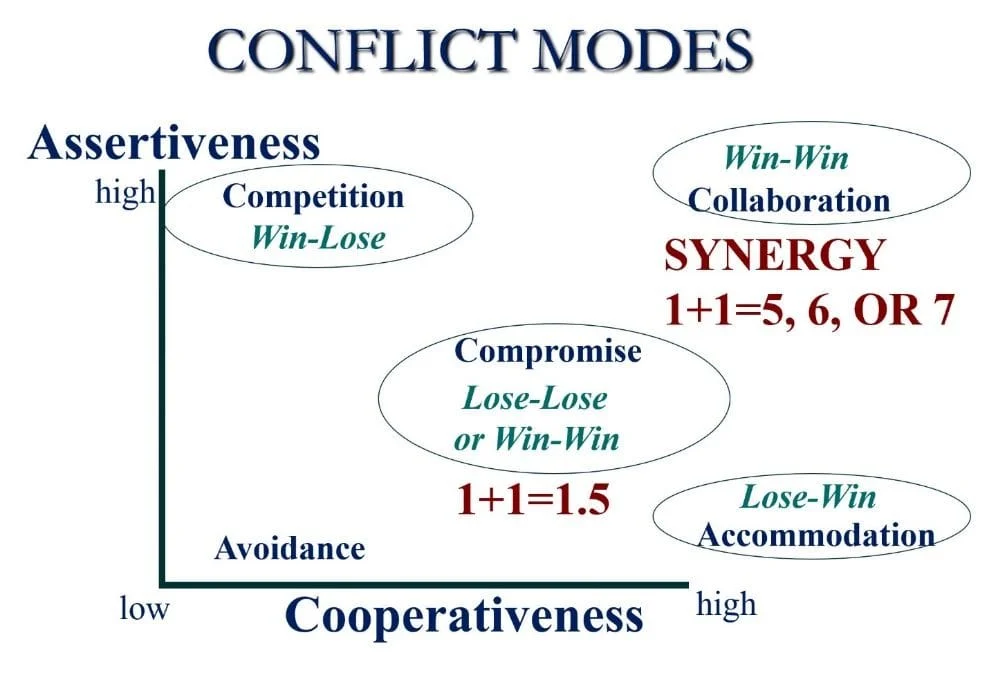

Another helpful idea is to choose your style of relating based upon the situation. What is your goal? Do you need to be assertive? Accommodating? Avoiding, Collaborating, compromising? As you can see from the following diagram, there are different possibilities.

Figure 17-3: Conflict Modes

A high level of assertiveness and a low level of cooperativeness leads to competition where one of you is winning and one of you is losing. A low level of assertiveness and a low level of cooperativeness leads to avoidance. A high level of cooperativeness with a low level of assertiveness is accommodation where one of you is choosing to give the other what he or she is wanting. A mixture of cooperativeness and assertiveness is compromise which may be very satisfying to both if you're both getting your needs met, or not satisfying at all if the intent is simply to avoid conflict. Collaboration results from a high degree of assertiveness and a high degree of cooperativeness and often results in synergy, results far exceeding the sum total of individual efforts.

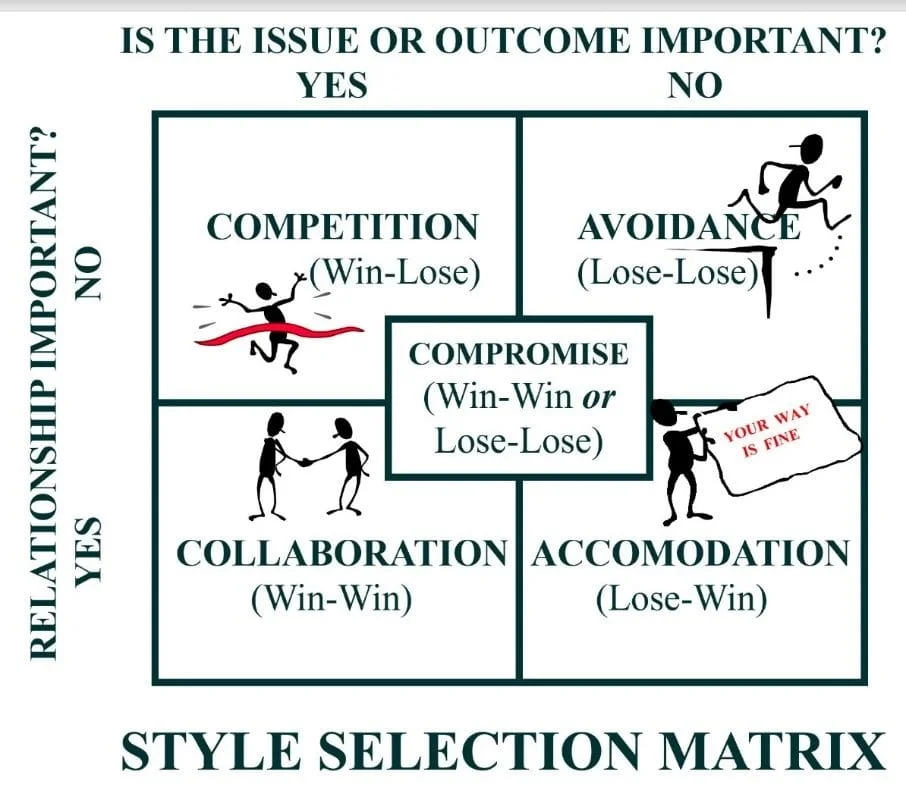

Should you always choose collaboration? Compromise? No, it depends on the situation.

So, how do you choose your mode of responding? Consider the following diagram. There are times when your style of conversation might be competitive such as when you are buying a new car. The salesman once you to spend more. You want to spend less, it's competition and that's appropriate. Competition, unless friendly and fun, is rarely a good idea in couple relationships.

Suppose you and your partner disagree on where to go to dinner. You got to choose last week and your partner has been really wanting a particular cuisine Accommodation would be appropriate.

Figure 17-4: Style Selection

Suppose you encounter a hostile driver on the road. Avoidance would be the best choice. However, avoidance of conflict with your partner usually means recycling the issue and hidden resentment leads to coldness and distance, as well as depression, anxiety, and lowered self-esteem.

Suppose you and your partner are trying to make a really important decision such as whether to have another child, or whether or not to move across country for one of you to take another job. In this situation, you need to talk at length and strive for consensus. Here collaboration would be the way to go, and dialogue is the perfect format..

Compromise is appropriate when the decision doesn't matter much and there are other things that are more important for discussion. Compromise and move on. However, be careful not to compromise just to avoid conflict, as the compromise will be short-lived and nothing will really be resolved. The best compromises take time and result from dialogue where each of you get to fully discuss your thoughts and feelings in a safe committed context.

The important thing to know is that when you and your partner have entered into dialogue, there is a range of possibilities. Sometimes, you may simply agree to disagree and that's fine as long as it's okay with both of you. If it's vitally important, keep talking!

There are four cardinal rules.

- Do not distance (“Walk Aways”)

- Do not coerce (“Power Plays”)

- Dialogue is caring, respectful, accepting, and validating

- Dialogue requires practice and skill, and also time and patience

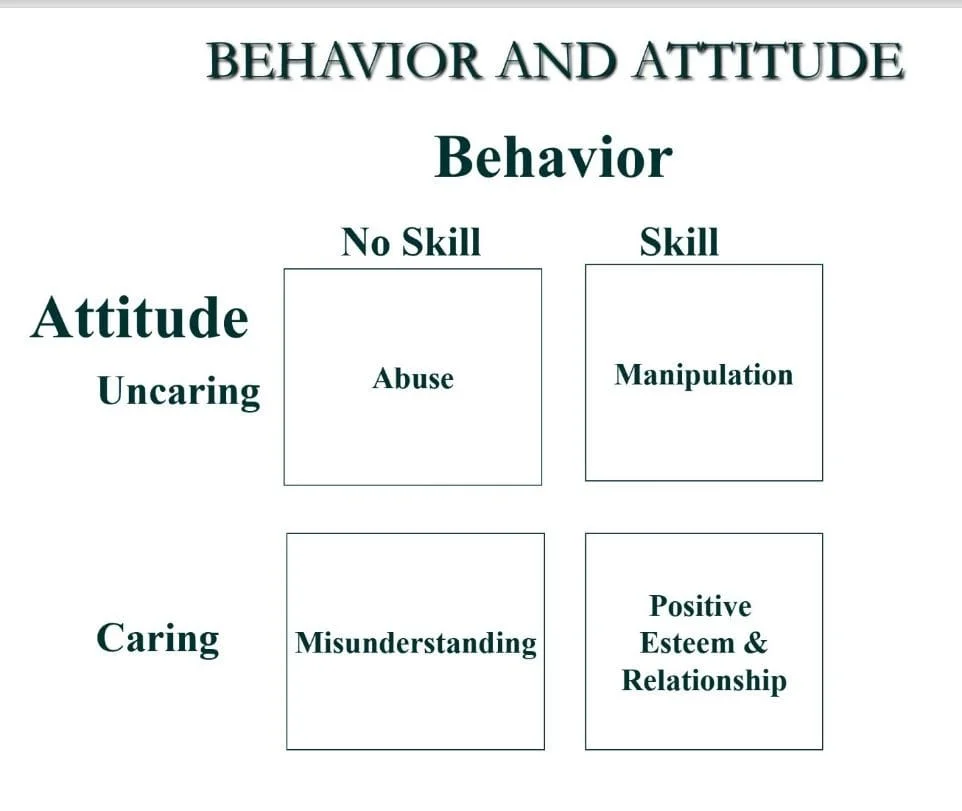

The following illustrates the convergence of caring and skill,

Figure 17-5: The Interaction of Behavior and Attitude

Behavior that is uncaring and unskilled is likely to be abusive. Behavior that is skillful but uncaring is a great way to describe manipulation. Behavior that is caring but unskilled is likely to produce poor results and is easily open to misunderstanding. What we want, and the main purpose of this book, is skillful and caring behavior – being the right Partner!

THE PIVOTAL MOMENT

Thirty years ago we were trained and certified in Imago Relationship Therapy. A central technique of this form of therapy is "the Imago Dialogue," a great practice for creating a conscious partnership. The Imago dialogue is a very structured approach involving three steps:

- Mirroring — paying close attention to what your partner is saying rather than focusing on your inner reaction to what is being said.

- Validation – affirming the internal logic of your partner's message. It's being able to say something like: "When I look at it from your point of view, you make sense to me."

- Empathy – a logical step following upon understanding what your partner is saying, and then affirming the logic of their feelings. Empathy is imagining what your partner's feelings might be and checking the accuracy of your guess. No one likes to be told what they are feeling so your tentative empathic guess needs to be verified by your partner.

While we use the Imago dialogue in our practice, and wholeheartedly invite our clients and our readers to check out Imago Relationship Therapy (Getting the Love You Want by Harville Hendrix), we work on getting our clients to develop a more informal dialogue option as a general and habitual way of speaking and listening to one another. We want couples to quickly recognize moments when important topics are up for discussion, feelings are strong, and their opinions vary. We want them to quickly and easily perceive a "pivotal moment" and shift to dialogue mode. With practice this shift becomes habitual.

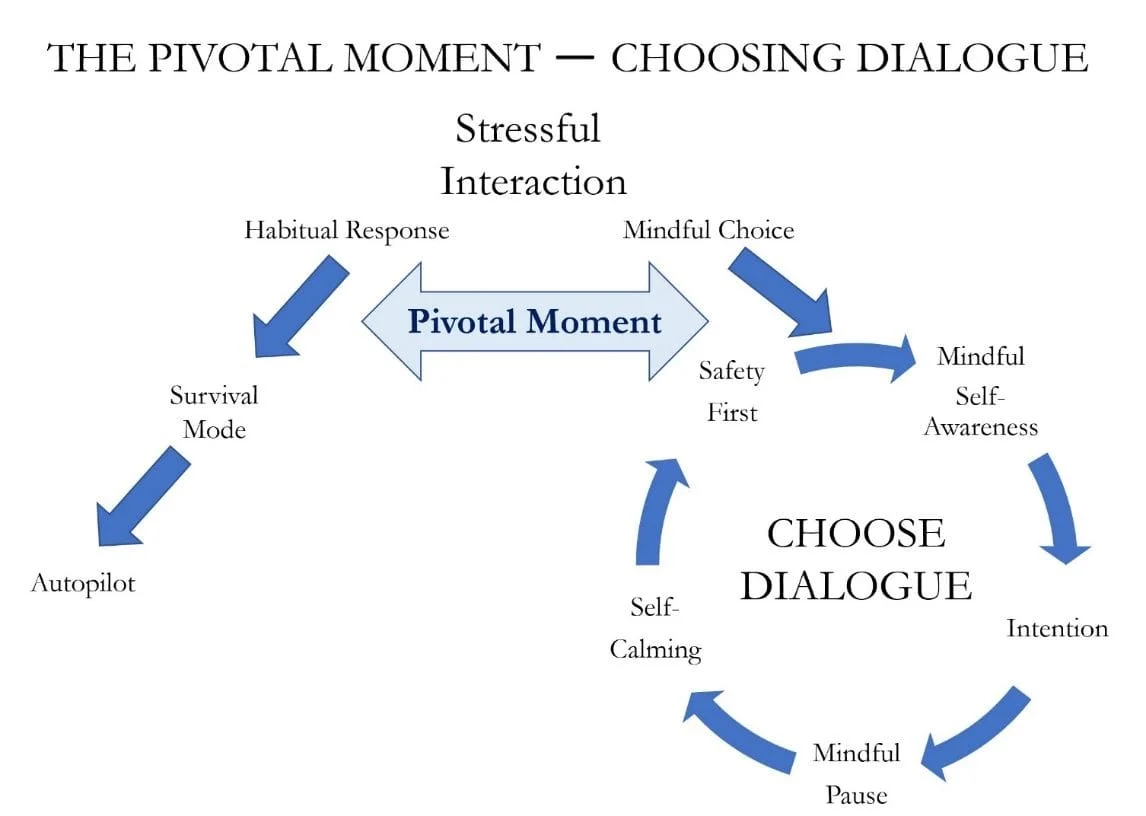

The following diagram is our conceptual mapping of “choosing dialogue.”

Figure 17-6” Choosing Dialogue

STRESSFUL INTERACTIONS: TWO PATHWAYS

It's hard to imagine being part of a couple without stressful interactions. Perhaps there is an absence of stress in the very beginning, during the period of romantic attraction and romantic love, when you and your partner are each on your best behavior, "making nice," and operating under the illusion that everything is perfect.

Sooner or later, reality sets in and you discover that you are with a different human being, someone who doesn't always think the way you do, remember the same event in exactly the same way, have the same goals, or have the same feelings. There is bound to be disagreement and conflict, and there are almost certain to be stressful interactions.

Most people respond unconsciously and habitually. You have a natural intention to avoid pain, and to the extent that you perceive your partner as dangerous, you may find yourself in survival mode – fight, flight, or freeze. Autopilot responses may block the connection that is fundamentally important to you, and ultimately these responses may jeopardize the relationship itself.

Visit the hallways outside of any divorce court you'll find them crowded with people who once loved one another, and perhaps still do. They just spent too much time, with too much intensity on the left pathway of the above diagram.

So here's a game changer. Develop a strong habit of making a mindful choice to slow down, calm down, and give up control, instead pursuing mindful self-awareness with the intention to take care of the relationship rather than choosing self-protection or ego.

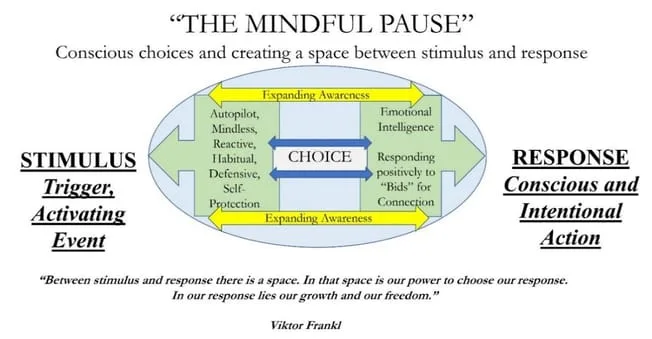

Imagine habitually taking a mindful pause as a practiced response to strong emotions and varying opinions.

Figure17-7: The Mindful Pause

Imagine utilizing your mindful pause to calm down and get in touch with which you really want out of the interaction. Do you want to be right? Do you want to win? Do you want to punish? Do you want to escape? Do you want to respond with emotional intelligence?

We're betting that at a deeper level you want connection more than winning or being right. You want a positive interaction, You want to build and strengthen your relationship. You want your relationship to be more satisfying.

Also, you want your relationship to be safe, not just for you but for your partner as well. Safety first! Be alert to signs that your partner doesn't feel safe and do what you have to do to help him or her feel safe within the interaction. Do not proceed until it's clear that both of you feel safe. Give whatever assurances your partner needs, to convince him or her that you genuinely want to understand and you are committed to being patient and respectful while they tell you everything they want to tell you. Safety is basic to dialogue.

Consider how language contributes to safety.

CLIMATE MANAGEMENT– CREATING SAFETY

Safety is a prerequisite for dialogue and safety requires a supportive climate.

An article by Jack Gibb entitled Defensive Communication that appeared in the Journal of Communication back in 1961 helps us to summarize the kind of Intentional Relating dialogue skills that make or break a relationship. Gibb wrote about the difference between a defensive climate and a supportive climate.

Choosing behaviors associated with a supportive climate greatly increases the likelihood that the other person will stop being defensive and join you in a collaborative team effort. The following chart lists both the defensive and supportive behaviors:

CONTRASTING CLIMATES

DEFENSIVE |

SUPPORTIVE |

evaluation |

description |

control |

problem orientation |

strategy |

spontaneity |

neutrality |

empathy |

superiority |

equality |

certainty |

provisionalism |

Remember, the goal is to get both of you out of a defensive mode and into being open, non-defensive, and willing to learn, ready to engage in dialogue. The language on the left side of the chart leads to defensiveness and resistance. The language on the right side leads to openness and is conducive to a collaborative team effort. The following is a brief description of each of these terms:

Evaluation language implies a judgment of the other person. Description language simply describes what has been seen or heard without any judgment attached. Dialogue is about describing what you are seeing, thinking, and feeling. Use "I language" rather than "you." This is owning your own experience rather than shifting responsibility to your partner.

When anger levels are blocking communication, descriptive language can help you de-escalate and move toward a cooperative exchange Comments such as "I see us getting louder and louder and more upset. We don’t seem to be getting anywhere. Can we back up and start over?" are more likely to be effective than evaluation statements such as "You’re impossible to talk to."

Control language implies what should be done while problem orientation language invites joint problem solving. A control statement such as "Everything will be fine when you agree to do it my way," will probably produce a defensive response. A problem orientation statement such as "I’m aware that we have a problem. I really want us to work together on this" is far more likely to pay off.

Strategy language communicates that the speaker has a hidden agenda. It's communication that sounds rehearsed. Spontaneity language seems natural, receptive, flexible, and generated on the spot.

Strategy lanquage might sound like "It will take us 30 minutes to discuss what I see as the only important aspects of the problem. If you found yourself on the receiving end of such a statement, would you feel welcome to fully discuss your viewpoint? Spontaneity lanquage on the other hand, could sound like "Two heads are always better than one. I’m interested in what we might come up with working together on this.”

Neutral is not a positive term as used by Gibb. Neutral language is cold, detached, and has an absence of feeling. Empathy language carries full acknowledgement of feelings and greatly facilitates open communication.

How does it feel when you have feelings you are eager to express, only to be met by a response that communicates a lack of warmth , caring , or emotional connection? Do you feel frustrated, hurt, angry? In all likelihood, you probably don’t feel very motivated to continue the conversation.

The word empathy originated with the Greek word empatheia and means entering into the feeling or spirit of another with appreciative perception or understanding. Statements such as "I have a hunch that you’re feeling attacked right now. Is that accurate?" can work magic in helping your partner feel understood and sincerely invited to share more.

Superiority language communicates to the listener that the speaker feels superior in some way. Equality language recognizes that situations and experiences are different and the intention is for differences to be respected.

A husband who states "I’m the one with the paycheck so I should have the most say in how it’s spent" will probably not get a pleasant response from his partner. He’d be far more successful saying "This is a partnership. We need to be a team in managing our finances. We may not always agree but we need to hear each other."

Certainty is characterized by thoughts or statements such as "I know I'm right." Provisionalism on the other hand, is typified by statements such as "Maybe I don't have all the answers. I could be wrong. I might be missing something. I'd like to hear what you think."

We could go on for many pages describing language skills that support dialogue and help you deal effectively with anger and conflict. There are skills to use when your partner is escalating in order to be heard ( empathy, validation ), with the result that anger is defused. There are skills to get at underlying issues and skills to use when anger is escalating toward a potentially destructive or even violent exchange. Most importantly, there are skills that help you move from an unconscious, chaotic and defensive interaction to the power and skill of dialogue and Intentional Relating.

CHOOSE DIALOGUE

How do you know when you are in dialogue?

You both feel safe. Neither of you feels judged. Neither of you is worried about your partner's reaction. Both of you are trusting that the relationship is strong enough to handle disagreement. Thoughts flow freely, with neither party shooting them down. There is an obvious commitment to hearing one another fully, without defensiveness or judgment. There is an absence of tension.

There is much mirroring, validation, and empathy,

Again, this is an acquired skill and may seem unnatural at first. However, engaging in dialogue can make all the difference between a failed or failing relationship, and a relationship that is alive and growing, a relationship that is thriving.

CHOICE 8–THE DIALOGUE OPTION

SELFASSESSMENT

DIRECTIONS: Under each description, choose the number that best represents agreement with your thinking, beliefs, or behavior for the past week and record that number on the following table (Also available on our website: www. Mindfulchoicesforcouples.com), or on the Mindful Choices for Couples Self-Assessment Scoring Sheet.

Important – do not respond on the basis of what you believe or intend. Respond on the basis of what you are actually doing or how much the statement typifies your actual behavior.

The Dialogue |

a |

b |

c |

d |

e |

Total Divided |

Option |

f |

g |

h |

i |

j |

by 2= _______ |

0= not true at all, 1= mostly not true, 2= partially true, 3= largely true, 4=totally true

a. I carefully choose my words with the intent of encouraging an open, safe and collaborative dialogue, rather than a climate characterized by defensiveness, resistance, or a "fight or flight" response. My language conveys empathy and equality, rather than cold neutrality and/or superiority.

Select 0, 1, 2, 3, or 4 and record on your table above or the Mindful Choices for Couples Self-Assessment Scoring Sheet.

b. I describe what I see rather than use words that imply judgement or blaming. I use descriptive messages that are clear and specific to de-escalate and move toward a cooperative exchange. I describe my feelings rather than attack with them. I avoid loaded words. I listen attentively, not reactively.

Select 0, 1, 2, 3, or 4 and record on your table above or the Mindful Choices for Couples Self-Assessment Scoring Sheet.

c. I choose language that implies an "us against the problem" approach (problem solving orientation), rather than language that only promotes my agenda (control language). I use inclusive language such as “we” or “us,” and I invite you to work with me on “our” problem.

Select 0, 1, 2, 3, or 4 and record on your table above or the Mindful Choices for Couples Self-Assessment Scoring Sheet.

d. I "go with the flow" using language that is natural, receptive, flexible, and generated on the spot, communicating a willingness to follow the conversation wherever it may lead and however it evolves (spontaneity language). This is in contrast to strategy language that sounds rehearsed and conveys a preset or hidden agenda, or an ulterior motive.

Select 0, 1, 2, 3, or 4 and record on your table above or the Mindful Choices for Couples Self-Assessment Scoring Sheet.

e. I demonstrate a willingness to be influenced by you, a willingness to be persuaded, even changing my mind if you are able to show me a new perspective, or show me something I've missed (provisionalism). This attitude is in marked contrast to certainty language that conveys a determination to stick to my own viewpoint, unmoved by anything you may want to contribute. I may have my own point of view but I invite you to join with me in exploring alternatives.

Select 0, 1, 2, 3, or 4 and record on your table above or the Mindful Choices for Couples Self-Assessment Scoring Sheet.

f. I use absolute terms very sparingly if at all. I am very careful about statements that begin with “you always…,” or “you never …”

Select 0, 1, 2, 3, or 4 and record on your table above or the Mindful Choices for Couples Self-Assessment Scoring Sheet.

g. I am careful not to make statements that impose my values on you such as “You should take environmental issues as seriously as I do”. While we no doubt have many values in common, we probably have differences in our values. I intend to respect yours.

Select 0, 1, 2, 3, or 4 and record on your vMindful Choices for Couples Self-Assessment Scoring Sheet.

h. I use sentences beginning with the term “you” very sparingly as they tend to be about accusations and blaming. Instead, I use “I” statements is much as possible, owning my own thoughts and feelings rather than implying that you have caused them.

Select 0, 1, 2, 3, or 4 and record on your table above or the Mindful Choices for Couples Self-Assessment Scoring Sheet.

i. I do not engage in mind reading, making definite statements about what I’m sure you are thinking or feeling. Instead, I may offer a guess or a hunch such as saying: “I’m guessing you’re feeling confused right now.”

Select 0, 1, 2, 3, or 4 and record on your table above or the Mindful Choices for Couples Self-Assessment Scoring Sheet.

j. I avoid cause-and-effect statements, such as stating “You made me very unhappy when you were late,” instead owning my own thoughts and feelings with statements such as: “When you’re late coming home I feel anxious.”

Select 0, 1, 2, 3, or 4 and record on your table above or the Mindful Choices for Couples Self-Assessment Scoring Sheet.

Category Total Divided by 2_____________(transfer to table above or Profile Sheet)

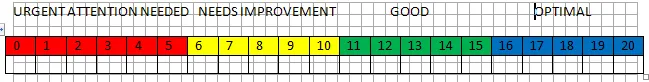

The following is an example of the table with squares a-J filled in with 10 scores, each square representing the 0-4 score on that particular statement. The scores are then totaled in the last square, for a total of 25 that is then divided by 2 for a final score of 12.5

|

The |

a 3 |

b 2 |

c 1 |

d 3 |

e 2 |

Total Divided |

Dialogue Choice |

f 2 |

g 4 |

h 3 |

i 1 |

j 2 |

by 2= __11 |

The score of 11 is then located on the grid below. This means that Dialogue Choice performance was in the “good” category. Overall, this means that the person taking this pretest was doing well with making a dialogue choice in his or her relationship. However, there is still substantial room for improvement. In fact, even with a perfect score there is no limit to how masterful you can become in choosing dialogue.

*

Okay, now it’s time to enter your score on the grid below.

How did you do?

THE THOUGHTS BEHIND THE 10 CHOICE 8 STATEMENTS

a. I carefully choose my words with the intent of encouraging an open, safe and collaborative dialogue, rather than a climate characterized by defensiveness, resistance, or a "fight or flight" response. My language conveys empathy and equality, rather than cold neutrality and/or superiority.

Safety first! If it's to be dialogue, take the time to make sure that you both feel safe. Ideally, you're striving for the freedom to say anything and everything while feeling fully sure that your partner will listen attentively, calmly, non-defensively, and respectfully.

Choose your words carefully. Be aware that there are fighting words such as "you never," or "you always." Emphasize to your partner that you want a dialogue in which you both feel safe, respected, and fully listened to.

In dialogue there is no room for sarcasm or harsh criticism implying that there is something the matter with your partner's character or personality.

b. I describe what I see rather than use words that imply judgement or blaming. I use descriptive language to de-escalate and move toward a cooperative exchange. I describe my feelings rather than attack with them. I listen attentively, not reactively.

If you seem to be evaluating your partner, you are probably creating defensiveness. Be very mindful of your facial expression, tone of voice or verbal content so as not to seem to be evaluating or judging your partner.

Here is the exception. If your partner perceives that you regard him or her as an equal and that you're just being open and spontaneous, they will probably not perceive you as judging or evaluating, or the evaluation part of the message may be neutralized.

This is tricky and it's hard not to sound evaluative at times. Invite your partner to tell you if they are feeling judged and give you feedback on how the message feels judgmental. Be curious and willing to learn, not defensive.

c. I choose language that implies an "us against the problem" approach (problem solving orientation), rather than language that only promotes my agenda (control language). I use inclusive language such as “we” or “us, and I invite you to work with me on “our’ problem.

If you sound like you're trying to control your partner, you're almost certain to get resistance. Dialogue requires the perception that there are no hidden motives, no imposing of a set of values or a particular viewpoint, or pushing for a predetermined solution to the problem being discussed.

Your language should be perceived by the listener as a sincere invitation to work together to find a solution to a mutual problem. The focus should be on issues, not personalities.

d. I "go with the flow" using language that is natural, receptive, flexible, and generated on the spot, communicating a willingness to follow the conversation wherever it may lead and however it evolves (spontaneity language). This is in contrast to strategy language that sounds rehearsed and conveys a preset or hidden agenda, or an ulterior motive.

Your choice of words and tone should convey openness and honesty. Your willingness to go wherever the conversation takes the two of you should indicate that your contribution is free of ulterior motives and is not following a preset plan.

Behavior that is perceived in spontaneous and non-deceptive reduces defensiveness and promotes openness and connection. Dialogue is the free flow of ideas and never involves coercion, manipulation, or heavy-handed persuasiveness.

e. I demonstrate a willingness to be influenced by you, a willingness to be persuaded, even changing my mind if you are able to show me a new perspective, or show me something I've missed (provisionalism). This attitude is in marked contrast to certainty language that conveys a determination to stick to my own viewpoint, unmoved by anything you may want to contribute. I may have my own point of view but I invite you to join with me in exploring alternatives.

We're not saying that dialogue means you don't have a point of view. Of course you have your own thoughts, feelings and opinions but dialogue means you also have an open attitude and a willingness to explore alternatives.

You can't have dialogue if you approach it with an attitude of certainty, seeing things in absolute terms, black or white. If you are perceived as having a corner on reality, you won't have a successful dialogue.

Dichotomous thinking is "either-or" thinking. In reality, you may both be right, but seeing the world from different perspectives. Dialogue involves a willingness to see your partner's perspective as neither right or wrong but simply different. This mindset is a precondition for validating your partner’s feelings– a foundational quality of empathy and dialogue.

f. I use absolute terms very sparingly. I am very careful about statements that begin with “you always…,” or “you never …”

There are few absolutes, death and taxes being two of them. In couple relationships absolute statements are often presented as obvious facts when they're rarely true. For example, imagine that your wife or husband says: "You never take out the trash," when you know that you rarely forget, although sometimes you need a little prodding. Chances are you will be angry and defensive.

How about you? Our suggestion is to largely ban the words "always" and "never."

g. I am careful not to make statements that impose my values on you such as “You should take environmental issues as seriously as I do”. While we no doubt have many values in common, we probably have differences in our values. I intend to respect yours.

Wars are sometimes fought over values, and some of the most difficult couple conflicts have to do with differences in values. Dialogue is a great way to examine different points of view. When there are values in conflict, but dealt with in respectful dialogue, values clarification may take place. You may find yourself with a sharpened awareness of your values, and you may even find yourself modifying values or choosing markedly different values.

In any event the important thing is to be respectful of your partner's values. Dialogue requires respect for values that may be quite different from your own.

h. I use sentences beginning with the term “you” very sparingly as they tend to be about accusations and blaming. Instead, I use “I” statements is much as possible, owning my own thoughts and feelings rather than implying that you have caused them.

Have you noticed that it's rather difficult to begin a sentence with "you" without pointing your finger. “You” messages tend to be blatantly judgmental such as: "You didn't return my call, again!"

“You” messages may also be seen as an attempt to portray the speaker as fully functional while implying the inadequacy of the listener. As a result, “you” messages often discourage interaction and foster defensiveness. Such messages may imply superiority rather than equality and are probably evaluative rather than descriptive.

We're not saying you should banish "you" entirely from your conversation. Just be aware of usage that takes you away from dialogue and gets you mired in nonproductive communication.

i. I do not engage in mind reading, making definite statements about what I’m sure you are thinking or feeling. Instead, I may offer a guess or a hunch such as saying: “I’m guessing you’re feeling confused right now.”

No one likes to be told what they are thinking or feeling. Offer a hunch or guess and then check it out by asking: "Is that accurate?"

Empathy statements are responsive to your partners feelings and thoughts but are stated tentatively if your partner's language is not explicit. For example, you might say: "I'm guessing that you're angry" if your partner has not clearly stated this emotion. Your partner will then tell you whether if that's accurate or not, and may add other feelings, or deeper emotions such as fear.

Couples often get focused and stuck on surface emotions such as anger, which is a secondary or surface emotion. There is always something deeper such as fear of abandonment, disconnection, or inadequacy. Having a deeper dialogue about deeper needs and feelings is powerful and can lead to real relationship healing and growth.

Dialogue takes you deeper into an exploration of deeper issues, primary emotions, and unmet attachment needs. Mind reading short-circuits this process and derails dialogue.

j. I avoid cause-and-effect statements, such as stating “You made me very unhappy when you were late,” instead owning my own thoughts and feelings with statements such as: “When you’re late coming home I feel anxious.”

Dialogue and accountability go hand-in-hand. No one else makes you feel your emotions. When you tell your partner: "You really pissed me off," you're putting all the responsibility and blame onto your partner. You made yourself the innocent victim to your partner’s misbehavior.

Actually, your thoughts and beliefs almost always come before your emotions. Consider the words of the first century philosopher Epictetus: "It's not the event that upsets you, but what you tell yourself about the event." Take responsibility for your role in the emotions that get generated. What are you telling yourself about your partner's words and actions?

We urge couples to use what we call "The Anger Formula." It involves a brief description of the situation, your emotions using "I" language, a specific request, and asking for feedback. Here's an example:

"When you come home late without giving me a call, I feel worried and angry. I'd really appreciate it if you would call me if you know you're going to be late. Is this something you could do for me?"

That's an example of whole communication. You could talk all night and not add much to that message. It's reasonable and you have a perfect right to make such a request. It doesn't come across as blaming and it's very specific in regard to what you want. The statement concludes with asking your partner if that something they are able to do, and will choose to do in the future.

This is the kind of communication that typifies dialogue, and dialogue typifies intentional relating and high-functioning couples.

What’s the next step?

It takes two to dialogue. Invite your partner to read this chapter and work with you in developing a dialogue habit.

Remember, not every conversation needs to be a dialogue. Often couples engage in small talk, light conversation that is important only in that it's part of their ongoing connection with each other. Sometimes communication is about imparting information and only requires a brief acknowledgment that the message is received and understood. Sometimes couples are simply socializing and sharing their individual experiences, perspectives, desires, dreams, etc. All this is important. So, use dialogue when it matters and make it habitual.

Dialogue is well-suited to the really important conversations such as deciding whether to have a baby, or move to another state. Dialogue is especially important when the topic is very important, decisions must be made, the two of you have very different opinions, and one or both of you is experiencing strong emotion.

All too often, couples get into heated debates that go nowhere. Dialogue may seem unnatural, but it's the crucial choice if conflicts are going to be resolved, and couples are to move beyond John Gottman's "Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse," criticism, contempt, defensiveness, and stonewalling— relationship destroyers. The cure is dialogue.

Tips for Improvement: The Shortlist

Cultivate the dialogue option and habit by revisiting disappointing interactions and viewing those situations that would have gone much differently with dialogue. Instead of getting stuck up your “ladder of inference” and playing the blame game, try figuring out what you might have done differently.

Consider dialoging with your partner about how to best use dialogue and develop the dialogue habit

Develop awareness of diffuse physiological arousal (fight or flight mode) as a way of reminding yourself that you need the dialogue option.

Practice breath awareness and breath retraining, following the guidelines in Choice 1 of the Mindful Choices for Well-Being material found on our website: www.mindfulchoicesforcouples.com.

Never, ever try to resolve a conflict while you are in fight-or-flight mode. You will simply make a mess of things. Get yourself first to a place where you are willing to follow the guidelines presented in these pages. Choose dialogue!

Focus on steadily improving your score to the “Good,” or “Optimal” levels. If you are working specifically on this choice area, take this short assessment on a daily basis utilizing the 31 day form found on our website. Re-take the Dialogue Option self-test from this chapter, as part of the overall Mindful Choices for Couples monthly assessment.

Choice 7 Personal Development Worksheet

Step 1: Identify a foundational value, or values. In other words, why is this Mindful Choice for Couples important to me? ________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Step 2: How would I describe my present Choice 8 performance?

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________Step 3: In regard to the dialogue option, what are the behaviors I want to change?

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Step 4: What is my personal vision for Choice 8? Imagining some point in the future. What Do I see myself doing in regard to Choice 8?

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Step 5: What do I hope to get from Choice 8:

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Step 6: To pursue Choice 8 to the point that I much more conscious and intentional in my relationships, how will I have to be in ways that might constitute a major stretch for me? Do I need a new way of being that would constitute a paradigm shift? Are there radically different ways of being (thinking, feeling, acting) that contribute to doing Mindful Choice 7 and getting what I want to get?

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Step 7: In regard to Choice 8, How will I have to act on a daily or ongoing basis so that I wind up doing what I want to do, and getting what I want to get, and being the way I want to be? How do I have to discipline myself to have consistent, routine, and well-practiced daily or ongoing actions that steadily contribute to the results I really want and value in my life?

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Step 8: What are the barriers such as negative self-talk or lack of time that might prevent me from reaching my Choice 8 goals?

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Step 9: Who will be helpful or supportive in my Choice 8change efforts?

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Step 10: How will I be rewarded while I am accomplishing the changes I desire?

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Step 11: how important is this to me on a scale from 1 to 10, with 10 being extremely important? How might I sabotage the plan, or allow others to sabotage the plan?

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Step 12: I am committing to the following SMART goal (Specific as to actions I will take, Meaningful and in alignment with my values, Adaptive in that I strongly believe my life will be improved, Realistic and achievable, and Time-framed with specific time dedicated).

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

References

Bohm, D. (2004). On Dialogue. Abingdon-on-Thames, UK: Routledge.

Gibb, J. (1961). Defensive Communication. Journal of Communication, 11, 141-148.

Gottman, J. M. (2002). The Relationship Cure: A Five Step Guide to Strengthening Your Marriage, Family, and Friendships. New York, NY: Harmony.

Gottman, J. M. (2015). The Seven Principles for Making Marriage Work. New York, NY: Harmony.

Gottman, J. S. (2014). 10 Principles for Doing Effective Couples Therapy. New York, NY: W.H. Norton & Company.

Hendrix, H. (2007). Getting the Love You Want. New York, NY: Henry Holt and Company.

Patterson, K., Grenny, J., McMillan, R., & Switzler, A. (2012). Crucial Conversations: Tools for Talking When Stakes are High. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.